On the road . May 2007 . Iran, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan

Globax Internet Club, Bukhara, Uzbekistan 22-05-07

From one holy city to the next, via the wild, wild west

Tehran to Bukhara

(11 cycle days; 4 rest days; 1 train trip; 844km; 1744m)

Tehran Mashhad (by train)

Mashhad to near Mazdaran (78km; 187m)

Mazdaran to near Gonbad Lee (86km; 510m)

Gonbad Lee - Iran to kilometer 57 in Turkmenistan (88km; 81m)

Kilometer 57 in Turkmenistan to road to Mary (88km; 133m)

road to Mary to Mary (93km; 73m)

Mary to near Zahmet (94km; 157m)

Zahmet to Repetek (103km; 314m)

Repetek to near Farab (89km; 146m)

Farab to Sayot (Uzbekistan) (76km; 108m)

Sayot to Bukhara (49km; 35m)

Whiling the time away

We have a few days to kill and the nagging

thought that our Sony Cybershot is going to produce

big black blobs in the middle of our Central Asian landscape

photos gets the better of us and we decide to purchase

a new camera. We initially had our heart set on the

Olympus E400 but the digital SLR choice in Tehran is

either Canon, Canon or Canon. You can however, find

the most amazing old SLR cameras, a mint condition Hasselblad

in it's original box and a super-8 movie camera still in the sealed plastic

wrapping. Prices are cheap and

the competition strong, so it pays to bargain. We purchase

the Canon 350D kit and although we'll need to upgrade

the lens at some stage, it's a really good start and

a comfortably compact and lightweight camera to use.

We wander around the city for as long as we can tolerate during the day and spend as much time as possible with our dear French friends before they fly out for Jaipur, India. Another cyclist from France, Didier, has joined the group waiting for Central Asian visa's. We go out for dinner, drink tea and have breakfast at Firouzeh Hotel a few times before waving Simon and Pierre-Yves off. We already miss them, but there are plans to meet up again sometime in the future.

Ali rings the embassy on Wednesday, but there's no word from Ashgabat as yet. We get chatting to Kokoro Ito, yet another cyclist: this time going in the opposite direction to us and embarking on a world trip as well. He puts us onto an address for a Shimano wholesaler in the north of Tehran. We first try our luck at the bike shops near the bazaar but they have no decent parts whatsoever. We taxi it out to the wholesalers: Saba Docharkh also known as Peugeot Cycles (16 Anahita St, Africa Express Way, Tehran 19176) and work out that it will be easier if we bring our bikes with us the following day. The showroom is something to see by the way and serious cycling must be quite popular with those that can afford the luxury in Iran. Niall rings later that evening to meet him at the Iranian Artists' Vegetarian Restaurant [Baghe Honarmandan, Corner of Moosavie St. and Taleghani Ave]. Since he could also do with a few spare parts, he decides to tag along with us tomorrow.

Nothing comes close to

Shimano

The ride out is reasonably busy in the

morning and it's a slow incline the whole way with a

couple of steep-ish hills to tackle. We arrive around

10.30am and remain in the building until well into the

afternoon. Our original plan was to get a couple of

spare chains and 15 spokes but we walk out not only with

them but a new back cassette, crank set and chain for

Ali's bike as well. All this gear cost only 55 euros. The time spent fitting everything

is a labour of love gift for us. All in all, it is quite a relaxing

and entertaining day, drinking tea and watching the

assembly line of bikes while ours are being pampered.

Going home is a breeze. Downhill all the way and as

it's Thursday afternoon the roads are completely dead.

I'm feeling a little lack lustre when we get back and

hit the hay quite early.

The dire-rear

I awake just before midnight with horrendous

stomach cramps and it's only then that the inconvenience

of shared bathroom facilities becomes obvious.

I spend the next 36 hours wishing my Mum was here to

look after me. I just know she'd cook chocolate blamange, grate granny smith apples and sprinkle brown sugar

all over them. Ali finds me lemonade, apples and brings

me a few banana milkshakes, which is a great consolation.

Though nothing tends to stay inside me long enough to do any good.

My time is broken up into intervals of 30 minutes of sleeping flat on my back and then making a mad dash to the Iranian loo. Probably the most irritating thing about the whole tedious ritual is having to put on long trousers, long sleeves and a head scarf every time I venture outside my hotel room. Once in the toilet, these have to be meticulously rolled up and held at bay. And while I am feeling so awfully sick, I am totally exasperated with the Muslim dress code. In the end, I just sleep in all my clothes even though it's stinking hot in our room. My scarf dangles ready in my hand. One positive thing to come out of all the tippy-toed toilet squatting, is my ankle feels a little stronger for it.

Ali takes the off-chance that the embassy is open on a Saturday and his speculation pays off: our visa has been approved for Türkmenistan and we can go the following day to pick them up. I'm still in bed feeling pretty miserable, when I hear the great news. The next day, I manage to drag myself to the embassy. The symptoms have subsided, but that might have something to do with the fact that I have nothing inside of me. I am feeling quite weak.

"You can come back tomorrow and pick your passports up" says the man behind the window. My heart sinks; not another day; we just can't. We're planning to catch the train to Mashhad tomorrow and I want out of here. Both Ali and Niall ask if it is possible to finalise everything today. "Come back at three" the official says. Okay, that's more like it and I breathe a sigh of relief. I can't get back to my hotel bed quick enough. While I sleep the rest of the day, Ali goes back at three along with Niall and both of them wait till four before getting served. After successfully picking up the passports, they decide to go to the train station to book the tickets for tomorrows journey to Mashhad.

Getting train tickets is a whole story unto itself. Put simply, you cannot buy one until the day of departure, unless of course, you want to book through a travel agent and pay a 20% service charge. Ali opts for cycling down the next morning and braving the queues, which takes him the good part of an hour and a half; even though he may skip the long line in front of the ticket window because a luggage carrier befriends and he is planning to travel first class.

Quite exhausted from his escapades, he arrives back at the hotel with the most expensive tickets. For the record, there are several grades of first class tickets but you are unable to stipulate which one you want and literally, get what you are given. We receive the 197,000 rial type that includes sleeping arrangements in a 4-birth sleeper, refreshments, dinner, breakfast and there's even a small television for entertainment. That's about the same price as a seat on the commuter train from Arnhem to Amsterdam in off-peak hours.

We pack everything on the bikes, wait for Niall to join us and all just hang around the hotel courtyard until five. Niall offers me his course of Ciprofloxacin for my stomach and they begin to work almost immediately, which saves me from what could be a nightmare train journey. If you don't already have them in your travel first aid kit, then I highly recommend you buying some. They are a wonder drug. At 5.00pm, the three of us weave our way through a typically maniacal Tehran peak hour towards the station.

Our passports are thoroughly controlled by the police and we are given the okay by the station master to take our bikes on board. Not sure what we would have done if he had said "no". Evidently, he has little communication with the actual train staff because it is not okay with them when we arrive on the platform. Today I'm a little frayed around the edges and sick of all the commotion about the bikes. I ask what the problem is to one of the attendants and he answers: "You can't put bikes on this train". I then ask "Why" and he returns a look of horror as if to say: "You can't ask why, just accept that you can't". He doesn't really answer my question and next thing I know, he has disappeared altogether. Other officials "umm and aaah" and debate amongst themselves and we are left waiting in anticipation until a last minute decision to place them next to the restaurant carriage is made. Always the same with public transport and bikes! There are three of us this time, so all the luggage and bikes make it on board no problem and quite safely.

The train, though not the newest model on the market, is really well decked out. There is tea, water and cookies waiting for us, when we enter our cabin. Orange juice follows a prompt departure and we get to know our Iranian travel companion: Benjamin. Around 7.30pm, the train stops in the middle of nowhere and its occupants - apart from us three - disembark and pile into a small mosque for prayer. By 8.00 pm, we are on our way again and a chicken shishkebab dinner is being served. The ride takes approximately 13 hours and we arrive in Mashhad at 7.30am.

It doesn't take too long before we find a hotel room for the three of us. Niall will stay one night only and then he's off to make his way slowly to Bajgiran before crossing into Türkmenistan. We are heading to the alternative border-post at Sarakhs, which is only a couple of cycling days away. Besides, we want to visit the Imam Reza shrine before leaving.

The truth about Iran

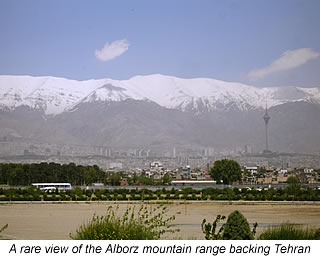

Probably the only reason most visitors

stay any longer than a couple of days in this over-polluted

and over-congested city is to obtain one or more visas.

Most of the travellers we meet seem to be suffering badly from

the visa blues. The symptoms are often relieved by taking

a bus to Estafan or Shiraz just to get out of, what after a short length of time becomes, quite a torturous city. It is then that you will find it a real shame that the bureaucratic

agencies don't move as fast as the traffic.

You can of course walk forever around the place, but who really wants to do that. After a few hours in the warm smog filtered sun you are completely knackered from dodging potholed pavements, open drains, pedestrians, street sellers and traffic. The latter, becoming easier and yourself becoming bolder with every street crossing you undertake. The trick is this: you just have to dare to step out in front of cars that look like they are going to bowl you over. They don't. They won't. They wouldn't dare; partly because they don't want the reams of paperwork associated with knocking down a tourist added to their already hectic lives and to be honest the drivers are pretty apt at handling their vehicles in Tehran. They know the exact width they can squeeze through without a centimeter to spare and the five lanes of traffic on the three lane highway is perfect proof of that. In a couple of taxi rides during peak hour, I took to looking everywhere, but out the front windscreen. It was way too nerve wracking. One consolation though, it is noticeable that all the cars seem to have very good brakes. I guess you wouldn't last two seconds on the road in Tehran with dodgy stopping power.

Commuter chaos & money confusion

Given the chance, a large percentage of taxi drivers

will try and rip you off. Most travellers know that

this is the case nearly everywhere in the world. In Tehran, you

are better off trying your luck along the roadside with

the locals than at the train and bus stations. Always

take the address written down on a piece of paper and

you'll find that most hotel staff will assist by writing the address in Arabic for you. This will help enormously with getting you to the destination you have in mind.

Tehran is ginormous and its network of freeways doesn't always make for direct routing. Therefore it can seem like you are being run around in circles. And there is a bonus of sharing a taxi with locals too: this way you see how much they are paying and can make an estimated guess of your fare. Some drivers will ask you to give them "as you like": in other words, whatever you think is a fair deal. One old guy did precisely this and when we suggested 30,000 rials - way over normal fare, by the way - he shook his head and said 40,000, which made us all laugh. Seeing as he was an entertaining sort of chap, we paid it anyway.

Negotiating a price can be very confusing since Iranians work in two currency units the Rial and the Toman: where 10 Rial equals 1 Toman. I think the ambiguity factor is obvious enough. So it is important to make it very clear during negotiations which one you are referring to. It is also a total fallacy that women and men won't share taxis. Given the choice, a woman will prefer to sit next to another woman, but that does not stop her from getting in a taxi with men. She will however, always take a seat in the back. Segregation is still mandatory on the buses: boys at the front and girls at the rear. Females even have to enter from the back. The modern 3-line - and soon to be expanded - Metro System has two women only carriages: one at the front and at the back. The rest are mixed, though you wouldn't know it. Very few females use these compartments.

One zone cost us 750 rial - about 6 euro cents - and that gets you to the outer ring of the CBD. A grumpy station attendant tried to rip us off and it took quite a bit of persistence on Aaldrik's behalf to get the correct money back. Clearly, this sort of behaviour is not just confined to the corner store, so do check your change wherever you go. It is a little habit of many cashiers to try and diddle you in transaction.

But back to the transport issue: whatever form you choose, it doesn't really matter, you will basically come away from the hustle and bustle and want to lock yourself in your room for a few hours of peace and quiet: other hotel guests obliging that is, but that is another chaos all to itself.

Khamenei's blind eye

There is a lot going on behind closed doors in Iran.

Sex, drugs and lycra do exist and they are all not that

difficult to get your hands on. In fact, while in the

bigger cities and towns, you might be offered

a quick nip of whiskey in a park or even invited to a party

where alcohol and opium are in plentiful supply. And

who would want to deny anyone a bit of fun every now

and again. After all the Iranian folk are human beings

too. It is just in the context of all those abayas, it seems

a little double standard. Rumours of Iranian women,

scantily clad underneath their hijab are the subject

of conversation with many western men. Well at least, I seemed to get caught up in such conversations.

I watch the eyes light up of a young Australian male, while he relays the story of a couple of young girls ripping off their black cloaks, once in the confines of their own home, to reveal fitted lycra outfits underneath. Another traveller excitedly tells me he was "flashed" during his day's expeditions. When asked what he exactly meant by that, he said he saw the hair of an Iranian girl. Now while this is an offense worthy of popping a woman in jail in Iran, it is hardly the cause for sexual arousal in a male from a western, non Muslim status.

Like the rest of the modern world, everyone in Iran has a mobile phone. And besides their obvious function, they are used for many other purposes too. Even though I was slightly shocked, don't be surprised if you see a man in a subway carriage, scanning through pictures of Clarissa with big boobs and then Samantha with even bigger ones. Or as a friend of ours experienced one afternoon in a cafe, a couple of men huddled over a tiny screen, intently amused by heavy breathing and groaning. Even with this somewhat public viewing of pornography, foreign males need to be aware that sex with an Iranian women is illegal unless you have permission to do so. Disobey this rule and you could end up in jail for 8 years or more. You can however, get a temporary marriage for such urges and although this is only hearsay, these matrimonial get-togethers can last just a few days or up to several weeks.

Some women in Tehran really do push the boundaries with the strict dress code and a feisty young student from the university told us bluntly how much she hated the headwear and other dress restrictions imposed on Iranian women. She and her friends do whatever they can to get away with the bear minimum of cover-up. Refraining from the use of makeup is also a rule that Iranian girls do not take much notice of. The windows of the women only carriage in the metro during peak hour is a mass reflection of faces adjusting scarves, preening themselves and adding a new layer of bright coloured lipstick or mascara.

Even within the confinement of their dress code, the women are amazingly fashion conscious and judging by the amount of garment shops in the bazaars and on the streets, shopping for clothes is a favourite past time. Though, all those beautiful strapless beaded evening gowns, tight-fitting tees and mini-skirts are only ever seen behind closed doors. Furthermore, though not quite the tassels and g-strings of an Amsterdam sex-shop, little playboy bunnies on brassieres and fur lined lacey lingerie are also on sale at market stalls. The shops are run strictly by males, so what seems completely bizarre to me is that while a woman in Iran must not show her hair, neck, arms or legs, she has no qualms about asking a complete male stranger for the pink lacy number in a 34C cup.

No gusht!

Vegetarianism is a concept literally laughed

at by Iranians. Honestly, we found that they didn't think we were serious at all and we encountered plenty of sniggers.

Veganism is almost incomprehensible and you will have

a hard time explaining this concept anywhere in the Middle East or Central Asia. So, unless you are prepared

to self-cater every single meal, you will either

starve or become pretty bored with plain rice for dinner every night.

After receiving so many bewildered and confused faces when trying to explain that we don't eat meat, I have resorted to drawing little pictures of animals contained in a circle with a "prohibited" cross through them. It is a more full-proof method than trying to reproduce a sentence or phrase not commonly used in a language you haven't yet mastered. And it is way more dignified than getting your message across in a restaurant full of locals with a series of farmyard noises.

The most common restaurant in Iran is not much more than a glorified kebab shop also selling a couple of oil layered, mutton based stews for those not into meat on a skewer. They will try and sell these meat pots off as vegetarian food by removing as much meat as possible, but after three failed attempts and repeatedly having to take the dish back to the kitchen, we have given up on even trying anymore. Therefore, the extent of our meal in eateries like these is a plate of plain rice, a bowl of yoghurt, flat bread and a soft drink.

Occasionally, we have bumped into a pizza snack bar, but mostly in the bigger towns. Providing the store doesn't use the prepackaged varieties, you can get something made without meat. There are also a few Indian restaurants scattered around for the mid-to top range budget. We were thankful that, our hotel in Tehran had a rooftop where we could cook our own meals, when we weren't frequenting the falafel shop down the road that is. Outside of the capital city though, these takeaway spots are not to be seen anywhere. The other place of salvation and divine dining refuge from boring, dry rice is the Coffee Shop and Iranian Artists' Vegetarian Restaurant [Baghe Honarmandan, Corner of Moosavie St. and Taleghani Ave and walking distance from Taleghani Metro Station].

Draped in a tablecloth

We couldn't leave Mashhad without a visit

to the Imam Reza Shrine, the second most holiest of

places of the Islamic world. In order for a women to enter, she must be completely covered and the Islamic Relations Office & Foreign Pilgrim's

Affairs offers the service of providing western women with a hijab for the visit. We enquire at the information

booth and wait a few minutes before a young girl arrives with

what resembles an tablecloth with three holes cut into

it: one larger one for the head and two cuffed in white

ribbing for the hands. It is the most embarrassing

garment I have ever had to wear. Well possibly on par with the boab tree costume

I had for my first and only ballet recital, when I was

six.

For a start, it was white with mauve flowers, similar in pattern to a piece of fabric your grandmother would use for her pinafore and secondly, it wasn't at all comfortable due to it's "idiot proof" elastic design. The least they could have done was make the thing black so I didn't stand out like a sore thumb. It is almost as if they think that a non-Muslim woman would not be capable of wearing the normal headdress and cloak. Anyway, my advice to female visitors: go to the local bazaar prior to a trip to Imam Reza and purchase yourself a cheap piece of black cloth or lend one from someone who you have befriended. You'll feel much more at ease.

Upon entering everyone is body searched. Cameras and bags are strictly forbidden to be taken into the complex and must be left outside at the gates. Mobile phones on the other hand are not prohibited, hence everyone is quite openly taking photographs or film on their Nokia. The tile work is quite beautiful though a lot of it is still under restoration and according to our guide will be until 2017. You are not allowed into the shrine itself but you get to watch a corporate video complete with the surprising American accented voice-over about the place. The visitors hall is noisy and bustling, so we can't understand all of what is said in the film, but we are given a complimentary copy to take away with us.

The Markazi Museum is an eclectic collection of rather obscure donations and some notable Iranian art pieces. Interestingly enough, artifacts only a few hundred years old reflect similar styles of middle ages art work of the western world. Our guide exclaims how beautiful a quite recently carved marble pillar is, since someone had crafted it by hand. "No machinery" he said. The piece is extremely rudimentary as far as carving is concerned and illustrates how insulated Iran is to the rest of the world. Had the man seen Greek or Roman sculptures dating back thousands of years, he might not have had so much enthusiasm. Similarly, a large 100 year old painting on display resembles something out of art history from the early 1500's. The contemporary pieces, however are surprisingly expressive and abstract and could quite easily find a place on the wall of any current-day art museum. The display cases throughout the museum held together with masking tape are not so modern and quite a sad contrast to the immaculate golden minarets outside.

New found friends and a

new found religion

You'll find that you adopt friends easily in Iran and they will

take it upon themselves to tag along with you wherever

you go. An Iraqi man did just this in Mashhad. It is

my birthday and Niall, Ali and I decide we'll try our

luck at finding a dvd for the evening. Our

new found acquaintance comes along, leading us all over

the place. He hasn't really understood what we want and after walking a few kilometres and a couple of taxi

rides later, we finally get back to the shop we first had in mind.

A few selected English movies are on offer: they are all copied onto Princo dvd's and cost just $US2 each. We pick out the French movie Priceless. It is time for dinner and the search for a place to eat begins. Our friend wants us to eat meat by the looks of the places he keeps dragging us to, even though we have explained that we don't eat any animals. He just laughs at us (well Ali) every time and before too long, we are content to enter yet another kebab shop with another plate of rice and yoghurt for dinner. To the complete astonishment of our company, Niall and Ali sing "Happy Birthday" to me and then I blow out the red rose plastic flower arrangement on the plastic covered table. I will certainly remember this birthday for a long time.

Back in our room, to my utter dismay, our Iraqi friend waltzes straight inside, uses the toilet and then plonks himself down on the bed, right in front of the laptop screen, ready to watch the movie with us. I have to perch way on the outside and miss out on seeing much of the movie. Even more annoying, I have to stay covered up until he gets bored and finally leaves: not without forgetting to mention that he will be back at 9.00am tomorrow.

And sure enough, the next morning he is there, willing to tag along. We have planned to venture around the town, while Niall wants to upload photographs and do a bit of surfing. He later tells us that his Iraqi friend sat next to him doing absolutely nothing for the entire two hours that he was in the internet cafe.

Another such encounter also happened during our stay in Tehran. On our fifth night, as I opened our hotel room door to go to the toilet, I find a guy outside, who has obviously been waiting there for goodness knows how long. He asks if he could come in and chat, which is, of course, fine by us. At least it is fine for the first two or three visits, but when the knock at the door becomes an every-evening event, or we return from dinner to find him outside waiting to be let in, it gets somewhat tedious. If he could speak better English, the conversation might go somewhere, but his use of the language is limited and we both find ourselves working like ESL teachers to keep it interesting. If we don't, it grinds to a halt and we all end up sitting there in complete silence, which is just as uncomfortable as me having to remain covered from head to toe in garments in my own little sweatbox of a hotel room. And after traipsing round town on visa runs all day, I'd prefer to relax in privacy. On one evening, I am not feeling particularly well and Ali refuses him entry, not without a major long explanation in the corridor and pleading with him to leave. He comes as per usual on the following night too, but after the same reaction from us, he doesn't return again.

Aaldrik has also stopped introducing himself as "Ali" because the line that then follows is: "Are you muslim?" Of course he answers says "no" and then the quest is on to find out what religion we are. No one ever seems to get any further than Christian or Jew: though what a Jew would be doing travelling in Iran beats us. Still, they always suggest it, like it could be a possibility. But besides these two beliefs, there just doesn't seem to be any registration of other world religions. Obviously, this is sometimes a tricky situation to be in and we don't like to openly admit that we are atheist, since being an atheist is not always associated with being a good person in the Muslim world. So, in a couple of circumstances, we have adopted Buddhism as our belief. At least our new-found religion does explain our stance as vegetarians quite nicely.

Disappointing departure

As we wheel our bikes out into the courtyard,

the ritual goodbyes and photographs become a little

disappointing when the hotel owner in Mashhad starts to beg for

money. The general belief, everywhere in the world, is that all westerners are overly rich and even though this proprietor

owns a hotel which is frequently visited and hence he earns himself an exceptionally decent

wage for Iranian standards, he still wants more. It is hard for people like him to understand that all we have left in the world

is a gradually depleting bank account and what is on

our bikes.

Getting out of the city takes quite a while and it reaches 32°C in the shade. Hot headwinds pick up after lunch time and they slow us down quite a bit. We are stopped by police on several occasions: once to film us with their Nokia mobile phone and all the other times just to practice their English. The landscape gets dryer and more barren with each kilometre. We pass many adobe house villages with small stalls standing roadside to purchase water from; all with varying prices of course. There are no large towns until we hit the border at Sarakhs. We pull off in a secluded spot on the roadside 25km before Mazdaran (78km; 187m).

The weather and views are similar today, though we are lucky to be minus the

strong winds. Every now and again large white tents decorate the harsh, barren landscape and like the herds of grazing sheep and goats, these are the only validation of life in this region. The road begins to deteriorate

markedly at the fork in the road. To left leads to Turkmenistan and right to Afghanistan.

There is little doubt in our minds which direction we must

take. It means a relatively steep 400 metre gain

in 34°C. heat.

After the climb out of Mazdaran, where we stop to get water, soft drinks and bread, there is a welcomed downhill coast. Another stop in the late afternoon for more liquid supplies and we decide to settle for the night 7km after Gonbad Lee (86km; 510m). That evening, as I watch a dung beetle expertly roll his treasure find past the tent, I contemplate the last month in Iran.

Without a doubt, it is a wonderful cycling destination. Beautiful countryside, challenging rides and outside the capital and surrounds amazingly peaceful and rural. Sure there are few negative points and some strange rules to abide by while you are here, but the people are so very genuine and on a level that I don't think we will ever experience anywhere else in the world. So the pros weigh out the cons by far. Though as I write this, I am relishing the thought of getting this sweaty head scarf off and allowing a bit of ventilation under my helmet and around my neck. Being able to sit by my tent at the end of a day's ride and brush the late afternoon's sunrays through my hair is a simple freedom I have very much missed during the last 30 days.

Proceedings

An early departure gets us to the border town, Sarakhs, before the full-on desert sun is high. We stock up on as much food and water

as we can possibly carry. The streets are full of persistent

beggars, but shop owners are friendly and trustworthy.

Ali thinks I have way too much food on board, but we will be grateful in days to come of our supplies.

From the moment when we enter the border zone, it will be exactly two and a half hours later that we actually make it onto Türkmenistan soil. The Iranian side is reasonably relaxed and we proceed rather effortlessly, though there is a short wait while the formalities are completed. A ride across a bridge with Iranian soldiers one side and Türkmen militia the other was also pretty painless, even if Ali does loose his lolly supply stashed in the top of his handlebar bag to a couple of sweet-toothed boys with AK47's.

The fun begins the moment a teenager in full army get-up, including gun, tells us to carry our bikes up a set of stairs and into a long rectangular room. The outside walls are white wooden panelling and the floor is concrete, which one worker gets the honour of sprinkling down with water at random intervals during the day to cool the building. Two small windowed booths are situated on the front left hand side. Directly before us, cutting the room in two and taking up an enormous amount of space is an x-ray machine and a walk through metal detector. A small desk where an official sits, blocks the rest of the pathway to the other side. Here, two long tables line the remaining side walls. At least five administrative staff members are perched on stools facing inwards, chatting and waiting patiently to use their personal brass stamps dangling on little fob chains. A few doors, kept shut most of the time, lead off to office rooms to the left and straight on.

Apparently, we have been given the wrong instructions and another official promptly orders us to take the bikes back outside again. We are told to sit outside in the entrance hall. After the usual "where you come from; where you go to" questioning, a custom's officer, who speaks reasonable English pulls us both individually aside to the first of the windowed booths. He thumbs through the passport several times before filling in an immigration card. He challenges my nationality because Ali had told him that I was born in Australia. His debate is that citizenship and nationality are unrelated. I beg to differ and say "I have given you my Dutch passport so I am therefore, as far as you should be concerned, Dutch". He doesn't like it, but fills in the form anyway.

Next, in the long line of proceedings, is the three step walk to the little white booth next door and what we soon learn is the bank. We need to pay US$10 each for entering the country, which we didn't know about and then a further US$2 each for having the man tiresomely fill in the handwritten forms in duplicate; that's four forms in total. He eventually accepts the 20,000 rial from each of us for his charges because we profess to having no other American cash on us besides a $US20 bill. These forms then go back the three steps to the original booth. Stamps are issued on all the bits of paper and we may proceed.

The bikes may now come inside, so we lift them up the steps for the second time and move towards the metal machines, where we are immediately stopped by someone else wanting us to take each piece off the bike and individually pass through the detectors. We object and explain it will take forever to pack and unpack the bikes. They insist, so I decide to play their game and take an amply bureaucratic amount of time untying a plastic bag from my back pannier. They eventually realise they could be waiting indefinitely and give in.

We are ushered past the machines and on to the right side of the building. Individual declaration forms are the following issue to deal with. Everything is written in Russian, so they need to fill them in for us, which is a bit spooky because we have to sign them. Of course, these need to be handwritten and in duplicate and I swear the guy filling in mine has never been to school in his life because he needed everything spelt for him at least three times by the other admin-worker peering over his shoulder and endlessly flipping through my passport at the same time.

Both sides need to be signed by the guy filling the form in and then endorsed by me. Further to this process, they are stamped by one of the administrators sitting at the long table on the left, taken back to the first booth and stamped a second time by the official we first dealt with and then given to the big boss for the third and last approval stamp.

These proceedings take a considerable amount of time as you can well imagine and while I am unsure of exactly how long, I am pleased when they keep one copy and hand over the other to us for our departure in seven days times. Well actually six and a half now. The white wooden doors are finally swung open, we clamber down the steps and ride not even thirty meters where we are stopped again to show our passports to the guys at the gate.

Ali changes money here and I rip my scarf off with sheer relief. It is a stinker of a day with 37°C in the shade, not that there is actually any shade to measure that in. We stop at a petrol station not far from the border and learn quickly that unlike most other countries in the world, they do not stock drinks or water of any shape or form. We also discover that the road to Mary is more like 250 kilometres instead of the 160 kilometres, we were led to believe from our map. As it is already nearly 2.00 pm, it means three cycling days instead of the two we had hoped for.

We continue on and stop at the next shady spot, which is created by a truck stopped and in need of a new tyre. The driver is Iranian and welcomes us warmly. He gets out a mat for the ground and offers us icy cold water from his refrigerator. It is delicious in comparison with the boiled stuff inside our Sigg bottles.

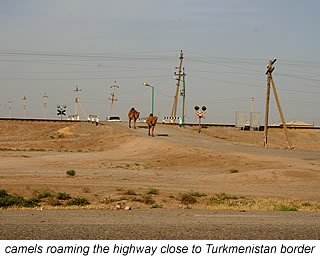

The whole day is broken up by mandatory stops at checkpoints and short pauses at every available bus stop along the way to rehydrate. Township populations come and crowd around us; especially the children. It is a totally different world here and a stark divergence from Iran. For a start, there are camels crossing the highway, the native women are clothed in beautifully coloured costumes, at control posts prostitutes are on offer, every mouth has a shiny set of gold, silver or both teeth, there are no signposts, no kilometre readings and the roads appear to have endured varying degrees of volcanic activity, resulting in a couple of very sore backsides after today's ride.

The sun is still very warm at 5.00pm. We actually leave tyre prints behind in the melting asphalt. Around 7.00pm we stop pedalling and find what we believe to be a nice spot hidden from the road in a vacant field at kilometre 57 in Turkmenistan (88km; 81m) Unfortunately, every insect in the vicinity thinks it is a nice spot as well and we end up lighting a small fire along with two mosquito-coils to try and and keep them at bay. All this seems to achieve though is creating a suicide pit for light driven beetles and praying mantis. Our legs and ankles are eaten alive by anything else that flies and bites. In contrast, we tuck into a meze dinner of sweetened butter sauted broad beans and onions and a spicy aubergine, pepper and tomato tagine served with fresh bread bought in Sarakhs earlier that day.

Operation desert storm

The wind picks up in the wee hours of the

morning and continues all day. It really has a good

try at shoving us back the way we came and we are slowed down

to a frustrating and energy zapping 7 kilometres per hour. I

can only think about one hour at a time: myself up front

for 15 to 20 minutes, then Ali for 20 to 30 minutes

and the rest of the 60 minute period is spend sitting on the side

of the road recuperating. For

six odd hours, we plod on like this.

We have started the day with very little water. Even though we entered Turkmenistan with nearly 5 litres each, the heat of yesterday's journey had its toll on our supply. There are no shops and only a few small rural villages from the border until Khaouz Khan. The only water available comes from the numerous fresh, flowing canals tapped from the Amurdarja River.

In the middle of a full-on sandstorm, we manage to filter enough for the day and then continue on with our battle against the wind. There are bus shelters at or near every small village which provide good refuge from the elements. At one pit-stop a battered old Mercedes pulls up and two uniformed men, claiming to be police, step out asking for our passports. Many male working positions warrant an official looking uniform in Turkmenistan and seeing as their outfits and vehicle are not quite up to the usual police standard, I am extremely dubious of their story. At first, we act dumb, but when they persist, we turn things around and ask them for their identification. This seems to do the trick and they promptly move on.

A golden rule in Central Asia - and the world over really - is to never give your passport to anyone, except at an official post or hotel. If someone asks you on the street for identification then show them a photocopy and say your passport is at your hotel. You can always offer for them to come back with you to look at it if they like. This will generally rid you of any unauthorised officers.

A few kilometres prior to the turnoff to the main road we find a side road leading us to Mary. The intersection, just before a petrol station and an Türkmen style arch, is marked by a giant Türkmenbasi poster complete with flags. The road is diabolical, but cuts off 15 kilometres or so and we are relishing the thought of the winds finally being in our favour. Unfortunately, they drop instantaneously and then it begins to pour. Cold and very wet, I wonder what curse has been placed upon us as we pull over to shelter in the conveniently placed service station.

Skies clear and we continue for as long as our bodies will hold out for. Well, actually it is my limit that usually depicts the day's limit. I think Ali could have possibly made a little more ground today. Right by the side of the highway there is a forested section of ground at 93 kilometres before Mary (88km; 133m) which seems our best option for the night.

Oh dear, Mary!

It rains all night and is quite a muddy affair the next morning.

You would think by getting closer to a big city that an upgrade on the road was

in order, but the Türkmen department responsible

for these sorts of decisions had other thoughts on the matter. We hit Khaouz

Khan mid morning and it is the first sign of real civilisation

for two days. The first service station, which you can't

miss, also has a hotel and cafe and we stop here for

supplies. Though there are more chances further on too, where the road is lined with

plenty of cafes. They all beckon us to replenish our

water and bread supplies with them.

While Ali goes into the cafe to get water, soft drink and bread, I shoot some film of the area and capture a couple of photos from a lovely gardener. I return to find Ali being helped out with his plastic bags full of drinks and bread by a Russian girl wearing a fitted beige petticoat revealing all her body curvatures including her breasts which are falling out of a one-size-too-small bra. As soon as she sees me, the bags are hurriedly dropped and she scoots back inside. Ten points for guessing what her occupation is.

There is nothing much between here and Mary. The cycling is roughly the same sort of bumpy journey as the last couple of days, though the setting is more rural and we have unusually overcast skies. We hit Mary (93km; 73m) in the late afternoon and are eager to find a hotel and have a shower. The first choice is US$56 for the night, which is way over our budget and any Türkmen's for that matter. Besides that, it is disgustingly dirty. In each hotel establishment we visit, there are two prices blatantly on display: one for locals and one for foreigners. They are all run-down and filthy, so we may as well choose the cheapest on offer. Sanjar Hotel is US$30 for us and US$3 for a local and the only words to describe the place are: grottiest dump on earth run by rip-off merchants, who then have the audacity to ask you to sign the guest book after they have taken your money and you have checked-out.

In comparison, the local pub owner is honest enough and we sample the piwa [beer] on tap. It costs 9000 manat: 35 euro cents for a pint. Local tradition moves one notch up on the volume level and everyone is purchasing their piwa in a PET bottle: BYO or the pub supplies you with one. It is really amusing to watch 1.5 litre pop bottles repeatedly being filled for 27,000 manat.

The cafe is in the middle of the town and a great way to unwind after an eye-opening wander around the colourful bazaar. Smaller thoroughfares show off rows of colourful apartment blocks shielded by huge sky dishes. Mary is full of bombastic monuments. Golden structures of totally insignificant function are embellished with Türkembashi's iconic poster. Actually every building, factory, gateway or place public importance is covered with his face. City streets are lined with colourful flower beds and fountains carefully tended to by hundreds of civil servants. These stretch for a good couple of kilometers outside of the town too where these six-lane boulevards are utilised by a small proportion of cars and buses in comparison to their traffic potential.

Rural friendliness

Only a few kilometres out of Mary and I burst my inner

tube which ends up wrapping itself around my cassette

and I come to a grinding halt. Quick enough repair,

but as we try and put the Schwalbe tyre back on, it appears that it has stretched somehow. We put our spare on.

One new tyre and tube later

and we are heading towards Merv.

At Bajramaly, we reach the turnoff to this historically important city which reached its heyday during the pinnacle years of the silk route - 11th and 12th centuries. It is a 4 kilometre ride to the entrance and once again local and foreigner prices apply. To be honest you could just cycle past the gate, without anyone being the wiser, but we stop. You are supposed to pay for using your camera and video as well and the English version of the pamphlet is double the price of the Türkmen copy. We go for the local version as it is the map we are interested in more than anything.

The cycle route is pretty nice in and around the ruins and a pleasant change from the usual days activities. Though, I could imagine some visitors might be disappointed with this once-great-city of the Ancient World. The eye-sore military base and radio tower we stumble upon in Türkmenistan's only Unesco World Heritage Site is a little bewildering to say the least.

We decide to cut across inland to Zahmet and not return back to the highway. It is all farming land: hot, flat and dusty with wide irrigation canals and some pretty rough tracks for roads. Everywhere we stop, we are enthusiastically greeted, given loaves of delicious bread and invited in for tea. One jovial farmer and his family of giggling daughters offers us a roof for the night. It would have been such fun to take him up on his proposal but we are restricted intensely by the 7-day transit visa and judging by the landscape so far, we envisage a tough two-day ride through the desert. So, after a series of photographs of the family, myself and a not so amused donkey, we reluctantly press on.

Everyone has been telling us about a large canal and bridge that we need to cross before taking a direct right, though exactly how far away that is has varied with every story. Nonetheless according to locals, we are heading in the right direction. Sure enough, quite a longer distance than anticipated later, we negotiate a rudimentary iron structure over invitingly cool flowing waters.

It is a long journey along even more dreadful roads than we have experienced so far, but the activity on the canal on our right makes for really interesting viewing. We reach Zahmet and a highway cafe, where we can stock up our depleted water supplies. Though not quite as far as we had hoped to get, a half hour or so down the road from Zahmet via Merv (94km; 157m), we pull over into the dunes. Finding a flat enough spot to pitch the tent, we set everything up, only to hear a man shout from the highway as he triumphantly lifts a fat, two-metre long snake in the air. Obviously, we keep our eyes and ears open all night.

A pub with a hole

Quite a distance needs to be travelled today and through a desert not quite as I had expected. Apart

from many small villages along the way, where

water could be sourced if necessary, there are also plenty of

bus stops for shade and rest. This is a major truck route after all, since it is the only bituminised - well, in parts - road from Mary to Turkmenabat. So, the danger of dying from thirst in this desert is not really on the cards. Üj-Ajy

is the only place along the way that really epitomizes the

perceived vision of a rolling dune desert. The rest is

grass and shrub clumped mounds.

The roads might be straight, but they are perpetually undulating and we face an infuriating wind the whole day. The sight of Repetek (103km; 314m) is a very, very welcome one. The group of Russian gas-oil workers obviously think the same thing about me and I am immediately dragged off to sit at their table and demanded to down a couple of vodkas in full jovial, raucous Russian spirit. Needless to say, I very, slap-on-the-wrist foolishly, have one to many shots and end up regretting the whole incident the next day especially while dry-reaching in the hot early morning desert sun.

We end up spending the night in a room off to the side of the 24 hour restaurant, in which they lay traditional mats and pillows for a comfortable night's sleep. While the hospitality is second to none, the fly population and the dug out hole in the ground overflowing with human excretion is a little hard to handle. Dung beetles, on the other hand, are having a field day.

The next morning around 10am, we leave the brunching Repetek staff to their meal. I get only a few kilometres down the road before having to stop and throw up the recently ingested water. This pattern repeats itself every 3 kilometres or so for the next 20 kilometres until I finally give in and sleep it off in a bus stop. I manage to keep some food down and we can continue along uninteresting sand dunes with the occasional herd of grazing camels livening things up.

By the time we make it to Turkmenabat, I have thankfully recovered. While Ali pulls a crowd outside the bazaar, I stock up with water and vegetables - fruit is outrageously expensive and limited. Getting out of town takes forever and there are further hold-ups at all the checkpoints crossing the Amurdarja River. Some guards enjoy calling you over just because they have the authority to do so and this gets extremely irritating when you just want to get out of the built-up area and find a nice quiet campsite.

Unfortunately, this quiet spot doesn't eventuate and we opt for an apricot orchard near Farab (89km; 146m), which is okay by its owner, but comes with a price. We are bugged by one local kid for the entire evening, wanting to touch and know about everything we own. He doesn't utter a word of English and we not a whisper of Russian, so it is a very elementary conversation. He finally disappears well after dark so we can deservedly sleep.

Türkmenbalderdashi

The locals are busy cutting down a tree inconveniently close to our tent the following day. We eat,

pack, and say goodbye to the numerous onlookers, as

well as give our over-curious little friend from the night

before a cycling t-shirt as a going away gift. It is

a 25 kilometre trip to the border, along a river and then down

a long stretch of lined-up lorries and keen money changers.

We make it to the gate at 9.30am on the dot. After Ali

changes some money, being let in is a cinch. The rest

of the procedure is NOT!

What we hope will take an hour, turns into a three and a half hour bureaucratic nightmare. Apparently - though the message was not relayed to us by any of the numerable Türkmen authorities we have met in the last month - we had to register after 5 days of our 7 day transit visa. Where we could have done this is baffling, because the desert has little in the way of official ports of call.

Anyway, it is Sunday and of course the boss is not in today. This results in having to wait for a phone call from him, which after an hour still hasn't come. I sit outside the Customs Office and watch swallows and cuckoos dart backwards and forwards over the barbed borderline. How easy it would be to have a feathered friend whisk me over this ridiculous human boundary; guarded by teenagers with initiatives as tiny as the metal cartridges designed for their machine guns and men with heads bigger than the pile of officious nonsense that exists in this country.

Ali is on the inside of the customs area and tries desperately to track down the soldier that initially told us that we had not followed the correct proceedings. He is no where to be found and another youngster bears the brunt of Ali's questioning. Eventually the kid has enough and organises for Ali to go upstairs to speak to the official that is holding up this process. No amount of pleading will quicken up the procedure and to cut a long and frustratingly tedious story short, we eventually get our passports back with a stamp banning us from entering Türkmenistan for another year. It was that or pay a fine.

In the meantime, Ali has handwritten and signed, in duplicate, two avadavats stating that we were not informed through the correct measures about this extra registration: one is for me; and one for him. Paradoxically these sticklers for detail allow him to sign on behalf of me, as long as he forged - yes their very words - my signature and didn't use his own.

We may now proceed with going through customs. We enter the wooden panelled double door, which a couple of brightly clothed women have barricaded with boxed goods of all dimensions they are trying to trolley across into Uzbekistan. Both of the thin doors need to be opened and the women move aside in order for us to pass. The Customs Officers now want to have their turn at holding us up. They check inside the panniers and I rather sarcastically offer them biscuits as I pull out the bag with biscuits in it, bread when they want to check inside that plastic shopping bag and so on until they get the message that I am only carrying food and cooking equipment on the back. Still, it is not enough for them to stop there and another person wants to check the front pannier. By some strange stroke of luck, I had packed our dirty washing bag in this pannier for a change this morning and as I open the draw-string, I hold it towards to the curious official, who plays into my trap and sticks his nose right into the bag. Being a hot day and having sat in the sun for almost two and a half hours, it would have reeked frightfully. At least, that is the impression I get, when he retracts his head as quickly as he stuck it in and motions that he doesn't wish to see anymore.

We have been standing in this thin 6 metre corridor, the width of a small double doorway for at least ten minutes. Our bikes lean against the wall on the right and small partitioned offices, the same width again, line the left. It is a total disarray of paper work and forms with men and women bureaucrats shaking heads, taking money and talking in overly-loud voices to overly-patient voyagers. We are finally given the go ahead to move a couple of metres down to the next window, where another stamp will be issued in our passport. This takes a further ten minutes and the guard with the machine gun at the end of the corridor is almost breathing down Ali's neck as he looks inquisitively on at the whole process. We wheel the bikes no more than one metre and although he witnessed seconds before the stamps going in, he still wants to check our passports.

Finally, we are outside and heading towards the freedom gate which is only about 20 metres away. We are stopped yet again and a boy soldier decides to take off with our passports and return to the booth behind us. The "banned from Turkmenistan" stamps have caught his eye and he wants to show them off to his mate. Ali yells at him to hurry up, at which he purposefully doesn't. By this stage I have had it. I've played sweet; I've waited; I've been patient, but this is now too much. I drop my bike; storm back to the cubbyhole they are hiding behind with big smiles on their faces and demand to have our passports immediately. I give them a loud and angry spiel about this ridiculous delay when I have to cycle in this blistering heat and how dare they think they can treat me like this. They have stopped me from making it to Bukhara in one day and anything else I could think of at the minute to blame on them. They promptly and quite sheepishly give the passports back with a quiet apology. We can now leave Turkmenistan, but not after an morning of complete balderdash.

Let's just say, the next leg of the immigration is easier and friendlier, though still tedious and full of duplicate paperwork. I think the "Welcome to Uzbekistan" and "May I see your passport please?" does it for me. This crossing takes just 30 minutes, but it is now well after 1pm and there's no way that we can make it to Bukhara today. We cycle on for 50 kilometres or so and since their are no other camping possibilities, settle once again for an apricot orchard in Sayot (77km; 108m)

Human zoo

The locals are upon us in a flash and it begins with

a small group of young boys, climbing and having fun

in the trees near our tent. They all want their photo

taken and we play along for a couple of hours or so,

quite amused by their childish antics and excitement

over the camera. We are pretty beat though, from the

days activities and want to wash down and change out

of the riding gear, cook dinner and then crash for the evening.

But even after shooing them away a couple of times,

they keep coming back. Each time, with new onlookers

from the nearby village. I'm sure the leader of the

pack is making money out of it. They won't budge either:

just stand right in the tent opening and stare at everything

you do. One cheeky little devil even takes to sitting

in Ali's seat when he gets up to do something . He is

promptly removed. Ali gets a little irate and they finally

get the message.

Not only are there children in the trees waiting for us to rise the next day, but 3 mini buses have congregated at the edge of the orchard. The sliding door is fully-open and half the occupants stare out at us while the other half have taken roadside seats. A small proportion of the village has gathered no more than ten metres from the tent and are discussing the state of apricot affairs, while keeping one of their eyes glued to us and our morning chores. Big Brother would go down a treat in this country, for sure.

Naturally, we are forced to leave without completing our toiletries and stop along a desert stretch to finish the morning rituals. It is only a short journey into Central Asia's most holiest city: Bukhara / Buxoro (49km; 35m) and we arrive around lunchtime. After checking the prices in some rather expensive hotels, Ali beats the price from US$25 to $15 per night for a spacious double room at Ramstan Zukhra [just up from Sasha & Son and right next door to New Moon]. Bathroom facilities though clean and with hot water, are a little on the pongy side, but the price also includes a breakfast to die for. A better choice might have been Madina and Ilyos's B&B [18 Mehtar Anbar St. Bukhara 705018], who we met after already settling in. They offer traditional accommodation with breakfast from $US5 per person per night.

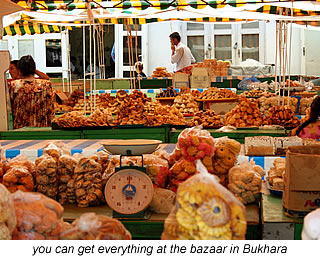

Bukhara, though very touristy, is quite magical due to its beautifully structured centre. Mosques and buildings of stone and colourful tile are vibrantly decorated by street vendors carpets, ceramics, silverware, puppets and embroidery. The atmosphere is quite stunning and it's a pleasant surprise to see new buildings going up in the same vein as the old ones. Lyabi-Hauz, the mulberry tree lined pool-fountain in the centre is a great refuge from the warm afternoon sun. Food is reasonably priced for western standards but beer is four times the local price. We have heard quite a few reports of upset stomachs from several travellers we meet after they ate here, so beware. If you need to do some grocery shopping, then definitely take the time to go to the bazaar in town, which is 20 minutes walk from the tourist centre. It is at least a third of the price of the mini-markets in town, who will do their utmost best to rip you off.

On our first evening in town, Niall cycles in quite late after a monster ride from the border. He looks completely beat and after a bit of catch-up chatter, we all hit the hay. It is no more that a wander around the town the next day and a general chill out since Niall is not feeling too well in the early evening and then I come down with the same thing early the next day. All this throwing up and diarrhea in Central Asia is getting a bit monotonous. Luckily, this bout only lasts 24 hours and we both put it down to an ice cream that we had both enjoyed. Or maybe it is really was the food at Lyabi-Hauz. Niall leaves late the day following, but we stay a further two days before packing up for the three day ride to Samarqand.

Plagued by punctures

Bukhara

to Samarqand via Qarshi

(257km; 1057m)

Bukhara to near Mubarak (113km; 311m)

Mubarak to Chardavar (101km; 358m)

Chardavar to Samarqand (43km; 388m; truck ride)

Desert camp

Due to the lack of secluded camping opportunities,

we decide not to take the main highway to Samarqand,

but the 50 kilometers of longer and hopefully more "off the

beaten track" cycling. We follow the A380 and turn off at Qarshi onto

the A378. This route takes us through

some real desert terrain and if you are embarking on it, take plenty of water

with you. Each of the next three days temperatures hang

around the mid thirties and there are little in the

way of shopping facilities. We have packed enough food

except for bread, but have to restock the water supplies

at every single drink stand we come across. Cooking

and washing included, we use about 6 litres of water

each and manage to slurp down at least 3 litres of sweet

fizzy liquid on top of that as well. That is a lot of fluids.

Landscape is barren and harsh though there are some decent wild camping spots along the first leg of the journey. We need to accomplish around 100 kilometres per day to make it to Samarqand in the estimated three days. Just as we are reaching this target today, we land in one of the longest industrial gas belts we have seen to date. It smells like someone is farting permanently and is very hideous to look at. When this view is almost out of sight, a small clump of shrubs a few hundred metres from the road also breaks the monotony of completely barren soil. We find a flat spot near Mubarak (113km; 311m); happen upon a lost tortoise, who unsuccessfully tries to disguise himself in a dried up box-thorn bush; and discover a scorpion's nest far enough away from the tent not to move, but close enough to keep me peering in that direction all night long.

Blown to oblivion

We are a mere 100 metres down the road

and like yesterday's start, we stop to repair a

flat. It is in the same spot as the last three punctures and the

only thing we can put it down to is a spoke that seems

a little long for my rim. We pad it with a bit of sandpaper

and it holds for the rest of the journey, though we have all

intentions of replacing it tonight when we find a spot

to camp.

The winds pick up around lunchtime and after the turnoff at Qarshi we confront them full in the face, for the rest of our journey. It is one long, tiring, unrewarding battle and we cycle at less than 10 kilometres per hour for the last half of the day. To make matters worse, the road is not flat and the 6% inclines are murderous to climb in these conditions. It is close to sunset when we climb the fine cement-sandy track just outside of Chardavar (101km; 358m).

We have a number of curious visitors, but I'm too busy sweeping away the not-earlier-detected double-gees [sometimes called goat heads] from around the tent, so Ali is left alone to go through the usual round of questioning. Even Superman was blown to oblivion today and I can tell that he really wants to be left alone. Eventually everyone leaves and we can get on with the usual chores before tentatively flopping on the mattress - in case we had missed a couple of those damaging prickles - and falling into a deep, deep "oblivious to nothing" sleep.

Lucky the truck blew in

Our attempt at an earlier rise than normal - to try and beat the headwinds - is unfortunately in vain. Mother nature is against us again. We struggle 35

kilometres in four and a half hours. Reaching the top of a hill, we are almost being

blown backwards. We know

instantaneously that we have been defeated and flag down a series of trucks

before finding one that will take us the 50 odd kilometres

up the road to Samarqand.

When we see the state of the road, we are so grateful to our two truckie friends. Vehicles can only travel between 40 and 50 kilometres and some craters require almost a complete stop to pass over them. Legally, only three persons are permitted to ride in the truck cabin, so I can only feel and hear most of the poor road conditions since I am stashed away out of sight in the sleeping compartment. It takes me back to teenage days when we used to sneak into the drive-ins by hiding under a rug on the backseat floor.

We make Samarqand (43km; 358m cycling; 46km by truck) by early afternoon and our drivers won't accept a thing for their troubles. We can't thank them enough and they pose quite proudly with our bikes in front of their truck. They are tickled pink by the attention from locals and having their photo taken, which we will send to them from Tashkent. They pull out and we only have a short ride into town.

It is a foregone conclusion that we are going to stay at Bahodir B&B [Mulokandov 132] as it gets rave reviews from travellers everywhere. Mostly for its friendly and relaxed atmosphere, but also dinner only adds an extra US dollar to the budget, which is a very attractive price for the meal that you get. Vegetarians will either have to find their own food or ignore the fact that the soup stock is animal based. The hotel lives up to its reputation of hospitable management, hot water, spacious rooms and a super relaxed common area where you can drink as many pots of tea as you like. That all said, the place is long overdue for a decent spring clean and on more than one occasion we are dished up stale bread at breakfast, which is included in the room rate.

The city of Samarqand can be absorbed quite easily in a couple of days and although its majolica tile work is quite spectacular and the structures superbly impressive, to me it lacks the magic and quirkiness that Bukhara has on offer. Other travellers feel completely different, but most agree that the entry fee into the Registan and mausoleum are comparatively expensive; equalling that of your overnight accommodation. The bazaar, in absolute contrast, is a bubbling exhibition of colour and excitement. Don't settle for the first price offer and be prepared to spend some time before it drops. We plan to stay four nights, but Ali once again falls victim to the same stomach problems that have been plaguing us both since Tehran and we remain an extra day. We leave for the capital, Tashkent on June 1.