On the road . December 2010 . Tunisia, Libya and Egypt

New Palace Hotel [website],

Cairo, Egypt, 04-01-11

Quick dash to the border

Kairouan to 14km after Ben Gardane

(5 cycle days; 1 rest day; 512km; 1182m)

Kairouan to 8 km after El Hencha (99km; 245m)

8 km after El Hencha to 3 km after Smara (100km; 195m)

3 km after Smara to Gabes (84km; 195m)

Gabes to Houmt Souk (116km; 344m)

Houmt Souk to 14km after Ben Gardane (113km; 203m)

Slow start to a fast finish

I should have read the early morning signs. The table we approach looks like six hungry animals have scoffed what they can and walked off leaving a disarray of food bits and service. I know the French do it too, which is probably where this habit originated from, but I find eating off the table quite discerning. Especially seeing as no-one in this hotel bothers to clean it down in between patrons. I push everything aside to make space for us and a man appears with a tray of breakfast items. It is customary in Tunisia that a pastry, white bread rolls, margarine, jam and coffee or tea be included in the price of your accommodation. He spies the two left over danish in the rubble of leftovers and fishes them out. For the next couple's breakfast presumably.Meanwhile, I battle with the pullback foil covering on the margarine portion and the muddiness of the overly strong black coffee. The wind howls like a spook-show ghost through an open window. This is not the day to go cycling 100 kilometres. I just know it. Ali on the other hand is adamant that we get to the border as quickly as possible. There might be some ambiguity about the dates on our visa, so instead of 12 days to get to Libya we have just 10.

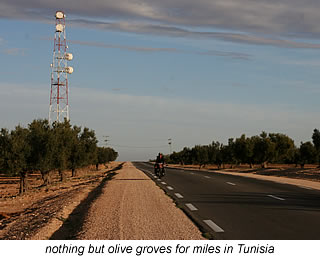

It is another hard slow slog against the wind and willing the mind to stay alert amid such repetitious olive tree scenery. Locals keep us awake though with their friendly hooting and tooting. One little kid runs a full 200 metres with me laughing the whole way. That kept me alive for at least ten minutes afterwards. El Jem comes into sight mid afternoon and there is just enough energy left in the legs to wander around the impressive Roman amphitheatre.

Hotel Julius, next to the train station is no longer in operation - at least not when we arrive - and we don't feel like deviating from our route and heading towards Sousse and Hotel Club Ksar El Jem, which is 4 kilometres out of town. So it is back on the excellent condition highway to have the wind completely about face and blow us south at a dazzling rate of 30 kilometres per hour. Such sensational riding, that it is almost a shame to stop and pitch the tent in a local olive grove 8 km after El Hencha (99km; 245m). Unfortunately, darkness is upon us by 5.30pm these days.

Carpet;

Coffee; they are all salesmen!

Apart from a few blatant attempts at trying to rip us off in Tunis restaurants

- where we stood our ground until we got the right price - Tunisians

have been incredibly encouraging with their energy, their smiles and

waves. Well, at least until this point in our travels. Though

I guess we couldn't really expect much more friendliness than watching

a local almost fall out of a tree with excitement and children pogo

dance to a rhythmic chorus of bongiorno, bongiorno.

Yes, there are a lot of Italian tourists in Tunisia obviously. And no,

it can't get much better than that. It was bound to go

downhill at some stage.

The morning is much the same as any other morning except we are gratefully minus the wind. We are pedalling along happily to the usual barrage of hellos and smiles of which one comes from a coffee shop owner at a petrol station. "Coffee! Coffee!" he screams gleefully and beckons us in. I could really go a caffeine fix and you never have to ask Ali, just pour one for him. Accepting the invitation, we about turn.

The first coffee is really good, so we ask for another, figuring by now that the gesture for a coffee is not a free one. The second coffee however, is quite horrible in comparison. I'm already expecting it before I see Ali shake his head when he is told how much the coffee is. You get this everywhere in Tunisia and it is something to watch out for. You ask for an espres and you'll get a Turkish coffee or an Italian espresso and not the average Tunisian espres you asked for. The difference in price is 4 fold, of course. It has happened so many times now that we just pay 500 per cup - the most expensive going rate for a local short black - no matter what. The coffee shop owner is not impressed that his little scam failed. We are equally not impressed with his sneaky ways.

Both disappointed, we cycle off immersed in our own thoughts.

One that pops to my mind is the amount of olive trees in this country. Tunisia has a population of 10.5 million, but surely they can't eat up all these olives. I initially suspect that Italy must be purchasing a few barrels to help with the cooking load over on the mainland and sure enough while checking the facts on internet, I find out that Tunisia has the second biggest area of planted olive trees worldwide and representing 19% of all global olive tree orchards. It is estimated that they have 56 million trees and I reckon we have seen almost all of them.

Tunisia actually exports about 66% of its oil production and a large part of that goes to Spain and Italy. So the next time you are at the supermarket thinking you are getting yourself pure Spanish or Italian olive oil, think again: there's probably a bit of Tunisia in that bottle somewhere too.

Besides these rambling olive grove thoughts there is nothing much else to report until we reach the equally rambling and ugly outskirts of Sfax. A long concentrated 12 kilometre effort is required getting into the centre, which for a brief interlude, is slightly more attractive. But we are soon cycling past more of that grey, dirty, industrial unkemptness leading out of the city. It is thankfully, not quite as long as our entrance was.

Somehow, the attitude of drivers has gone back a few notches on the courtesy and evolution ladder. Besides pushing on the horn incessantly, they push the limit with their maniac behaviour. Fruit farmers set up roadside stores all selling the same looking pears, pomegranates and plums. All stacked in little metal pails, just big enough to overflow with 2 kilos of fruit. Prices are competitive, but I'm not prepared to haggle; had my fill of salesmen today.

Another olive grove becomes our campground 3 km after Smara (100km; 195m).

ICS: Irritable Cycling Syndrome

Mist sits

low and long this morning and it is only just clearing as we push

the bikes over sandy red rivets to reach the highway. The din of

traffic continued all night long and although it is slightly bearable

this early in the day, by the time late afternoon comes and we are

finishing for the day, I've almost reached screaming point. We have

been whizzed past dangerously close, at great speed and at great

risk to oncoming traffic, but then again they head straight for

us too in kamikaze overtaking stunts, forcing us onto soft shoulders.

I've shrieked and yelled and given a few quite obviously infuriated

hand signals. I've also questioned Ali a million times if there

isn't an alternative route.

There isn't, so it has been a trying day. Spirits are lifted a little as we make our way past the colourful marketplace of Gabes (84km; 195m). They sink slightly when I see the state of the campground we traipsed all over town trying to find. Once we have cleared all the fallen dates out of the way, we have a semi-decent spot for pitching the tent. The toilet amenities will have to stay in their appalling condition I'm afraid. I go as far as tying the shower's water pipe to the wall with some dental floss, but that is about it.

I wander into town for a spot of shopping, amusing the entire local community as I do so. They are always curious as to what I buy and similarly surprised to find out that I purchase the same sorts of things they do. When I get back, a market store owner has seized the opportunity to befriend Ali and leave behind a few token gifts in the hope we will purchase a few blocks of amber soap off him when he returns. Like yesterday, I'm in no mood for haggling or salesman banter so we do purchase some amber soap & he leaves us alone under the date trees to get on with our chores before night falls.

A little blue and white island

Starting off in flying form, with a little help from the wind, we

breeze along the GP1 to the MC118 turnoff. While we might be heading into more peaceful

road territory we now face a strong side wind. We push hard past petrol

sellers and a few crazy dogs as the highway winds its way through

desert-like landscape. It takes all afternoon to reach the ferry

boat to Île

de Jerba. Once on the island, here is still another 20 kilometres of pedalling to

do before reaching Houmt

Souk (116km; 344m) and only an hour of light left. We can't

find the hotel we are looking for and just ask at the first one

we can find. It is only 20 Tunisian dinars including a rather simple

breakfast, dodgy shower fittings but a piping hot one in a presentably

clean room. A fine as any place to rest for a day.

Wandering around the entire town doesn't take too long and while parts of the souk are definitely geared towards the tourist trade, the rest, at this time of year, is pleasantly normal.

A few camels lighten the mood

We are up early, eager to have breakfast and leave for the 100 kilometre

plus trip getting us as close to the Libyan border as is feasible.

The only catch is, no-one else in the hotel is. Tunisians are very

late risers - so are Libyans and Egyptians for that matter, as we

will later find out. Even with the early 5.30am call from the mosque,

most people rise, wash, grab their mat, do their prayers and then

crawl back to bed again. Which then leaves us with the choice of

stumbling in the dark over a pile of men sleeping in the lobby

and missing out on breakfast - not that it is so spectacular - or

making enough noise in the place to stir the staff back to life

and into the kitchen. We leave well fed and a half hour later than

expected at 7.30am.

The wind is slightly against us from the beginning and enough to slow me down to a speed that Ali finds irritating. He argues that we will never make it, but if my calculations are right, we will. Landscape is of the usual olive trees and sand and pretty boring really. We have an equally boring quarrel regarding my pedal rate again and we cycle apart for a while. The caravan of camels cause us to stop in the same place and they are certainly a mood lightener. You can't help smiling at such silly faces as they graze and ponder our presence.

The ride only becomes interesting as we enter Ben Gardane and are looking to finish for the day. It is bursting with activity and colour like any border town with souvenir salesmen, ceramics, stuffed toy camels, leather sandals, carpet and fluffy blanket stores - North Africans seem to have a fetish for bright gaudy coloured furry blankets. Why I cannot say, but they are on sale everywhere and always draw a crowd anxious to run their hands over the plush pile.

There are also lines of money changes waving wads of money and there's something untrustworthy about someone flipping a fist full of money in your face beckoning you to "money change; money change". But these guys are legitimate enough and give a really good exchange rate. After a quick stop at the ute full of mandarins, we are off to find the first best camp spot along the roadside.

A police control point inspects our passports with thoroughness a bit further on and just before we find a patch of trees - actually more difficult than it sounds - 14km after Ben Gardane (113km; 203m). Sun retreats only just a bit quicker than we fall asleep.

Hathor

Hotel [website],

Aswan, Egypt, 26-01-11

Hathor

Hotel [website],

Aswan, Egypt, 26-01-11Libya - on a breeze and a prayer

14km after Ben Gardane - Tunisia to Tripoli - Libya

(11 cycle days; 804km bus trip; 3 rest days; 1059km; 4436m)

14km after Ben Gardane - Tunisia to Sabratha - Libya (124km; 141m)

Sabratha to Tripoli (78km; 218m)

Tripoli to Al Khoms (123km; 435m)

Al Khoms to Misrata (92km; 113m)

Misrata to Benghazi (804km mini-bus trip)

Benghazi to 2 km after Tukrah (81km; 256m)

2 km after Tukrah to 7 km after Qasr Libya (89km; 751m)

7 km after Qasr Libya to Al Bayda (41km; 516m)

Al Bayda to 22 km before Al Tamimi (145km; 753m)

22 km before Al Tamimi to 7 km after Knightsbridge Cemetery (105km; 311m)

7 km after Knightsbridge Cemetery to 6 km before Qasr al Jady (103km; 296m)

6 km before Qasr al Jady to Salloum - Egypt (78km; 186m)

The Libyan five minutes

Getting

out of Tunisia is almost as difficult as getting into Libya. We pedal

up to the Ras Jedire [Ras Ajdir] immigration - a glass booth stuffed

with a couple of computers, strewn bits of paper and

three guys. One of them is definitely the boss and he is as arrogant

as the questioning is ridiculous. "Where

are you going? And after Libya? And after Egypt? And after Turkey,

you go home? Why are you cycling? What 's your

job?" Like any of this is relevant. We just want to

get out of the country, not in.

The important one obviously gives the okay for each and every passport that comes through this border, which accounts for the process being so darned slow. He refuses to give the nod to the guy handling our documents. In fact, he takes no notice of him altogether. Someone else of importance is called in and the interrogation begins all over again. After twenty minutes, they realise that we are not spies on bikes and the stamp goes down on the page. We can now leave. Well, at least we thought so.

No sooner have we turned the wheels four revolutions and: "Stop!"

"Stop? Why?" asks Ali.

We get

the signal

to pull over to the side.

Again Ali questions: "Why?"

"We

are douane. You know douane? Different immigration," comes

the rather agitated reply as the guard makes an attempt at letting

us know he is also important. It appears there might be a bit of

departmental rivalry going on at Tunisian frontier lines.

"Yes I know you are douane, but why do

we have to stop. We are going into Libya and we need to hurry up," says

Ali.

"You have alcohol?" one guy

questions as we turn our bikes around preparing to cycle off.

"What? Do you think

I'm crazy?" Ali replies. One of them waves us on and

we leave before any more stupid questions can be thought up.

We enter the immigration area of Libya. Green corrugated plastic sits atop thick grey concrete walls. Sun pours through rectangular slits about camel height, but the atmosphere is still dark and oppressive. The line of three booths with white blocked-out glass is where all the activity takes place. There are important people: dressed in blue military suits, black shoes and carrying either a walkie talkie or a big silver stamp. They meet and greet each other as if they have just come back from a six month holiday: kisses, handshakes, shoulder claps and plenty of excited smiles. There are unimportant people too: dressed in tattered robes, a dirty head scarf, disintegrating sandals on their feet and either lugging some great bundle or pushing their wheelbarrow of possessions. They are poe faced and silent. Every now and again a commotion starts. The important people scream at the unimportant people, pushing them back from the immigration booths. They sometimes hit them too, but mostly they just yell a lot.

We are also unimportant people, but of a different nature. We have a transit visa for 14 days in our passport and every important person here has to look at it. It is obviously unusual. It goes from one booth to the next and back again, finally getting transported by a guy with one of those big silver immigration stamps into a brick building layered with dusty LG fans. "Five minutes", says one official.

We are still standing in the hot burning sun when one of the important guys grabs my bike and starts riding it around. An equally important friend video's it on his mobile. I don't push the situation and ask if I can too, though it would have made for great footage; especially considering, my tiny framed bike actually fitted this guy. The men are not that tall in this part of the world.

In this burning sun position, we ask after our passports three times. Each reply is the same: "five minutes".

We move over to a shaded area by the side of the boom gate. It

has been nearly an hour and time to pull out a few border control

tricks. I sit on the pavement, spread the tea towel out like a

picnic blanket and proceed to prepare food for lunch.

"No,

no. Problem, problem!" says a young important lad.

"

What problem?" I say. "You keep me

waiting here and I get hungry. I will therefore eat."

"

NO, not here. There." as he points to the burning sun position

in the gravel.

"

I'm not sitting there" I say. "It is too hot and it is dirty. I will eat here."

Someone

quickly disappears inside, but returns with the answer: "five

minutes".

Ali then makes out he is going to walk

straight into the building himself.

"Stop, NO!" says a guard.

"

What

stop no?" replies Ali. "You

don't tell me what is going on. You have our passports and I

want to know what the problem is. If you won't tell me, then I'll

go in and find out myself."

Another

guard goes inside.

Again the return reply is: "five minutes"

Libya is not used to having many foreigners enter her country and especially not those that have been given permission to roam the country at will - well coastal areas at least, though we were never told we couldn't go anywhere else. Being closed for years, Libya officially opened its doors to tourism around the turn of this century, but within 12 months and after some tourists were supposedly caught with archeological treasures stuffed in their bags, independent travel became a thing of the past. Travelling through Libya now, meant having a guide breathing down your neck for the entire length of your waking day, and as well as feeding and accommodating him, you also had to pay a whopping fee as well.

Since then Gaddafi has implemented enough changes in regulations to keep tour operators on their toes and have guide books skeptical about what they should actually put to print. A few years back, all passports suddenly required an Arabic translation and more recently the great leader banned citizens of 25 European countries from entering Libya in a counterattack against the arrest of his son, Hannibal Gaddafi, and wife in Geneva. They were accused of assaulting two domestic servants in a luxury hotel and after a tit-for-tat political battle between Libya and Switzerland, things soon returned to their same fickle self.

The whole visa application process for Libya is a global mystery and without real guidelines so, it is difficult to know how you should go about it. Of course, it hasn't stopped tenacious independent travellers from trying their luck at getting a transit visa and hence the intrepid few have actually been quietly dribbling in and out of the country for the last decade. Everyone of them however, has a different story to tell about the procedure, but one thing remains unanimous: if you want to visit Libya without a guide, then sit tight. It is one big waiting game.

Obviously, so is trying to get through immigration control, even when you have the long awaited visa stuck in your passport. Our mood is swinging towards mega-frustration and we constantly nag the important people. Without us knowing, our documents have somehow managed to slip back to one of the three booths at the entrance. After 90 minutes we, or should I say Ali, is permitted to go and get them.

We are far from gliding out of the bureaucracy loop. Another booth; another important person; and then another: "Stop, passports!"; gets in the way of our freedom. This time the police need to check that everything is in order. Photocopying our visa and arabic translation cannot be achieved without a short drive to another building, where they have a machine capable of such a unique task. "Five minutes," they say.

While the police are doing their paperwork, Ali sneaks off to find a bank. I settle in for the duration of the Libyan five minutes to watch the parade of human mules move towards the Tunisian border carrying weighty boxes of electronics strapped to their bodies. It looks like excruciatingly hard work, so I gather electrical goods must be cheap in Libya. When we are finally allowed to cycle on, I pop our leftover Tunisian coins in one of these living-transporter's hand. His old wrinkled face gleams.

Mad Dash

Our immediate reaction to the long stretch of reasonably

quiet highway, is of excitement and adventure. We feel elated

and privileged to be here; to be cycling in Libya and to be

without a guide. Our thoughts soon become absorbed with reaching

Sabratha before nightfall. The delays at immigration coupled

with the highway becoming fast and furious at Zaltan, only

40 kilometres after the border, mean we have to cycle

like speeding bullets to reach our goal. Sadly, it means we

cannot stop and talk to all the people that beckon us in for

a cup of tea, nor to all who try to flag us down from their

cars. It is one mad dash.

A dash along a 4-lane highway, where at one intersection it becomes clear the country is minus one of its camels. I guess a truck was at fault by the way it was spread out across the asphalt. A further dash through Zuara, 60 kilometres after the border, with its unusual housing of symmetrically stacked Escher-style boxes. A dash straight into Sabratha and up to the crossroads, where a policeman stops traffic from all directions to let us through. And an escorted dash down a poorly lit road to the Hostel International in Sabratha (124km; 141m).

Even if we weren't feeling hungry, tired and annoyed about having to wait for more than half an hour on the front porch before someone turns up to help us, we would still say the Youth Hostel in Sabratha is grim. We refuse to sleep in the cabinet like rooms with no roof and secondhand linen and instead camp outside in the football pitch for 5 dinar per person. The toilets and showers are downright offensive and there is no separate facility for women, which in these all-male operations, is quite intimidating. I keep thinking every time I walk past the reception area with its square ring of chairs occupied by men drinking tea and smoking cigarettes, that if each of them put in an hour's cleaning work per day, they could keep this place in some sort of reasonable order.

Jeremy Clarkson territory

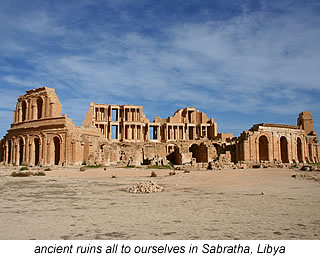

Sabratha is even more stunning

than either of us could have possibly imagined. So is the

crystal clear day back dropping the ancient city. I am so

overwhelmed as I move closer to the world's most well preserved

Roman theatre, I remember my heart pounding. I just sat in

the circle benches and caught my breath. I could have

applauded loud and clear. It was certainly worth it and

there was no-one around there to think I might be crazy.

Seeing something like this in such glorified completeness

is a unique experience, but to be here with no-one

else in sight is a true honour. An honour I will never

forget and will remain the highlight of travelling in Libya.

I could have spent all day wandering around these ruins

snugly nestled off the shores of the turquoise Mediterranean

Sea, but we have a capital city to embrace and at 11.00am

it is back on the bikes.

From the serenity, we drag ourselves back onto the hell-raising road. Each car is like a rocket launching itself right past your ears. Libyans are total speed freaks and Jeremy Clarkson would be rapturous should he ever get the chance to visit this country. Not only is the petrol dirt cheap at 12 dinar cents per litre [7.2 euro cents / litre], but everyone drives like their car is fitted with a turbo-charged engine. I never knew that a Honda Civic could rock along at 150 k's per hour. It does in Libya and what's more, there's a woman behind the wheel too.

There is no break in suburbia from Sabratha to Tripoli. The day is one long hard pedal punctuated by pleasant welcomes and hellos from locals and only one feral stone throwing incident. The highway condition gets progressively worse as we close in on the capital and we really have to fight for our space where no shoulder exists. Areas of industry ditch their debris roadside and I come to a screeching halt after not being able to avoid a sharp metal strap. It cuts straight through my back tyre and tube. Repairs take forever, when our newly acquired Road Morph Master pump decides to play silly-buggers. Back on the road, it is still not much fun and the city centre just never seems to eventuate. There are hardly any signs to follow or enlighten you where you are either.

The guy manning reception at the Hostel International in Tripoli prefers to sleep rather than attend to customers, even though they are banging hard on the office window. He doesn't wake when they both call out at the top of their lungs either. One of Ali's whistles finally gets his attention, though now acting offended, he refuses to serve him. We have no choice but to move on in hope of finding a cheap hotel. That is like searching for a needle in a haystack.

It is no wonder Gaddafi puts his tent up everywhere he goes. Accommodation in Libya is way too expensive for what you get. The bottom of the barrel tourist hotel we find in Tripoli (78km; 218m) with the help of a well-meaning taxi driver, is 60 dinars [35 euros]. He first took us to a 180 dinar place, thinking that we would consider that cheap. People really do have a distorted perception about wealth in the west. Our budget will only stretch, though quite begrudgingly so, for the stained sticky carpets, archaic bathroom that needs a good old scrub and run-down veneer furniture in a room at Hotel Marhaba. Breakfast is surprisingly decent and set up as a buffet where you can go back for seconds. We exercise this right with a passion.

Much of our rest day is spent finding another mini dv video camera. Our choice is limited to one shop and one camera, but the price is cheaper than in Europe and the Sony DCR-HC62 actually turns out to be a little gem. The sound might not be brilliant, but the image is sharp, the zoom steady and there are enough features to adjust for different lightning and unusual situations. While we are contemplating the risk of parting with 445 dinars [270 euros] in a far-off land for a piece of electronic equipment, we wander around the Medina [Old City] with its strong Ottoman influence: brass and copper goods, traditional dress and dazzlingly intricate bead work contrast the stark whitewashed walls.

Tracking down a decent bike store in Tripoli to replace my back tyre proves a more difficult task and although there is a small bicycle shop on the second block on the left as you walk up Avenue Omar Mukhtar from Martyr's Square, it has nothing much of use for us. The fresh produce market place on the corner of Sharia Khalid ibn al Walid and Sharia an Nasr near the San francisco church has plenty on offer, but shopkeepers are not particularly trustworthy when it comes to their prices. This is the first and the last time I will experience this in Libya. Everyone else was not only honest, but usually helpful once they got over the shock of not only a foreigner, but a woman stepping inside their shop. Men, especially in rural areas, do the shopping in Libya, not women.

Just cycling from A to B

The morning starts off promising. It is Friday; a weekend day

in the Islamic world and there are only a few other travellers

on the immaculate 6 lane highway leading out of Tripoli. The

green grass, palm tree lined perfection lasts for about 20 kilometres

and then we round a bend hitting a double lane where the shoulder

has been deliberately etched with grooves and the usual countryside

views return. Traffic increases as the day wears on and I get

progressively more irritable too. Cycling is only about getting

from A to B. The scenery certainly isn't very inspiring: farmland

and rubbish; citrus stores and olive trees; bags of peanuts and

jars of oil mingle in with a blurry sea of trucks and cars. People

are friendly enough, but the intensity of such concentrated pedalling

counteracts each and every good feeling moment you receive.

About the best point in the day is turning off towards Leptis Magna (123km; 435m), 5 kilometres out of El Khoms, and finding the Tazweet Camping sign. For 5 dinar each we get a grassy patch and hot shower and the chance to meet Ahmed: a big hearted Moroccan man who runs the little cafeteria on the campground and who knows how to make a mean turkish coffee.

After the impact of Sabratha, we are a bit worried that Leptis Magna might disappoint us. But we needn't have troubled ourselves, it is just as amazing, even bigger in size and indulgence and totally incomparable. We are early enough to wander around alone for an hour or so, before a handful of tourists join us in this massive ancient site with their guides. I am as happy here as Jeremy Clarkson would be on Libyan highways. The place is monumental in showing how splendidly opulent Roman architecture can get. If the extravagant decoration doesn't have you "wowing" at every corner, then the sheer enormity and complexity of the city will humble you for sure. Well worth the 6 dinar entrance fee. Rumours of compulsory guides are untrue for those of you who like to wander freely and at your own pace.

Where have all the women gone?

Yesterday's experience in the supermarket up the road

was bizarre. I was again, the only woman in the shop. I was

probably the only women who had set foot inside this shop

in months. It was clearly a males' affair. So, where have

all the women gone? I saw one Arabic female at the ruins,

but the others were all foreigners. She was hobbling along

the uneven surfaces in her dainty sling back stilettos, the

rest had sandshoes and socks on. Probably the strangest

thing is, when I do see a local women clad heavily in her

black drapes, she usually turns away from me. In public places,

there is no tallness or pride about their stance. It is

a sort of hunched-over, cloaked-scurrying to get somewhere:

secretive, hidden, hasty. What is there to hide from another

woman? Is seeing a foreigner too confrontational? Is it forbidden

in Islamic law to say hello to a woman from the western world? Or are they all just scared?

Today, I see just one woman smile.

Everything starts off pretty good, with a super early start and our parting gift of two omelette rolls from Ahmed at the campground café. He is a gem: not only having helped us find new o-rings for our cooker in town and kept an eye on our tent, he is genuinely sweet. The highway is on and off. On: meaning rideable on the shoulder; and off: implying we had to plough our way along a moon-like crater. Like every other day in Libya, traffic just gets increasingly worse as the hours tick on. We do fly along though, making Misrata (92km; 113m) by 1.30pm. Another half an hour is spent riding around trying to find the bus station.

We pull in and within minutes everything is confirmed: the ride to Benghazi including being dropped off at the Buyut Shabab [Youth Hostel] at Sport's City. The latter is paramount since the 820 kilometre journey means we will arrive around midnight. It costs 20 dinar per person and 10 each for the bikes. Libyan share taxis work on roughly 0.50 dinar for 20 kilometres.

I then try to find a shop and a toilet. All the men totally ignore me, when I ask in the bus-station office. Turning their heads away, they continue talking to one another. I stand there waiting for a reply. I enquire a second time at which point, a young lad directs me to a local shop where I can buy bread. The toilet is across the road, but the attendant, a large, rather unkempt looking man with noticeably filthy fingernails motions that it will cost me 1.00 dinar; or at least that is what I understand. The state of the toilets is about as clean as the guy at the entrance, so I renege and go back to the van. Ali decides he wants to go and change out of his riding gear for the journey. He returns saying it is only 0.250 dinar and the old man is asking after me. Of course he is, because he doesn't want to miss a prime opportunity to grab hold of me when I attempt to leave the premises. It is not so much the intrusive sexual grope that upsets me, as me having let my guard down. If I were in India, I would have seen this scenario coming. No, I would have expected it and acted accordingly. But up until this incident, I have not had any problems with men for a very long time. I had simply wound down the protective shields. D@mn it!

I don't mention it to Ali, who would have, no doubt gone back and tried to thump the bulky beast. In hindsight, it might have been a better idea to get everything cleared out there and then, instead of allowing the resentment to stew and bubble inside my head and taint my trip to Benghazi.

Our chauffeur drives like a speeding bullet: that much I had expected after our cycling experiences in traffic, but only having two music tapes is surprising and over the course of the evening, incredibly irritating. Listening to the same songs over and over again with their atonal rah-tah-tah-yah-yah-aye repetition really nibbles at your nerves. We pull into the roadside cafe, where our driver obviously stops customarily on this journey from Misrata to Benghazi.

Desperately in need of a cup of coffee and a change of scenery, I walk through the barrier and into the all-male domain. Every single person stops, turns and stares at me. It is an unavoidable entrance, and whether I had a scarf on or not, horribly intimidating. While Ali gets the coffees, I keep my eyes pinned to the menu in front of me. Alone, I wouldn't succeed in getting served in this place. Just trying to get a spoonful of sugar from the bar later on is hard enough. In general, men don't move out the way much for women and they often pay no attention to their requests. Since I am already feeling vulnerable after today's physical harassment, I don't have any inclination to squeeze into a bunch of Arab men.

The menu is cheap. Coffee is 500 cents and meals don't go much higher than 4 dinar. It is even in English. You can get Kintaki 2 piece, which is obviously a chicken dish or Scaloob, a word which has eluded translation to this day. The four men next to me eat only with one hand. Tearing a chicken apart requires skills of barbaric measures and bits of meat and fat flick everywhere as one man struggles to rip the wing bone from the carcass joint. It gets me to wondering if the guy that skewers the birds for the rotisserie only uses one hand as well. It would certainly make becoming a chef in the Islamic world a pretty unique form of education. Maybe he wears plastic gloves while doing it. Though, if he doesn't then isn't the chicken already unclean before it reaches the table?

Perusing the room, my surreal position as the only female in miles, becomes more apparent to me. I'm bordering on feeling angry at this inequality in numbers. I cannot wrap my brain around the fact that women don't travel by public transport in Libya. When I discover that there is no female toilet available at this road-stop, I realise just how narrow-minded the whole situation is. Even so, I am still left with the genuinely real question: where would all the women go? Behind the building? Nah, too risky. I just hold on.

I walk back to the van where six of the male (adult) passengers are playing around with each other like a bunch of school children. No one talks to me. They are not unpleasant, they just overlook me. For the entire trip I hear nothing from them. Not even a hello. They have no problems chatting with Aaldrik though. My bicycle has become slightly loose and we get a couple of bungy cords out to fasten it tight again. The driver is becoming increasingly grumpy and tries to take off while Ali is fixing the bikes to the roof rack and before another lad has emerged from the toilet.

Back in the taxi, we are further familiarised with our chauffeur's limited taste in music and kept on the edges of our seats with some wild Schumacher style overtaking. The road is under construction constantly along this desert section and we are reduced to a crawl on numerous occasions too. Military checkpoints have either been super easy, or had a couple of power attitudes that just like to be annoying. Our documents are all in order, so they can't really stop us from travelling this way. Besides, it is more a "showing you who is boss" performance than anything else.

Broken promises; broken wit

Nine and a half hours after leaving Misrata, we are

entering the outskirts of Benghazi. It is 12.30am and

I can feel we are heading straight for a problem. The driver

comes to a stop at the taxi office and everyone piles out. Another

broken promise: I just hate this side of travelling. Once they

get your money, they do what they like. Ali gets out to inform

him that he still needs to drop us off at the Youth Hostel. He

just says "finished".

We would never have taken a journey that would arrive at this time of night in the middle of a strange city with fully loaded bikes, had it not been for the promise they would deliver us to the door of our overnight accommodation. We confirmed this three times with them before we agreed to get in the taxi. Now, however, everyone is arguing that our story is impossible and that we are, basically, lying. I sit quiet in the van, listening to the conversation going nowhere. How could he even think about leaving us here in the dark of night, in an unfamiliar place, not knowing where the hell we are with 14 bags of luggage and two bikes. This driver is no better than the guy manning the toilet at Misrata bus station, since he is prepared to make me feel just as vulnerable. What is more, he is male and I'm about done with the all dominating attitudes I have experienced today. I get out of the van with my video camera and I flip.

I mean, I really flip in a big way. I scream. I rant. I scream some more: right close up in his face and at this point in time, I don't care at all. I hate him. I hate him for making me feel so defenseless. I film him and the others telling us we have to figure it out for ourselves. I thank everyone sarcastically for their hospitable nature. The camera doesn't go down well and in hindsight, in Libya, it was probably not one of my more brilliant ideas. I'm not particularly proud of my actions, but I suppose I'm attacking in the only way I can and with a gusto that has been festering since earlier on in the day.

We start pulling our gear out the van and someone, somewhere in the group must have taken stock of the situation and understood what a ludicrous and susceptible position they were putting us into. Immediately, things are reversed and we are sitting in the van heading towards the Youth Hostel at Sport's City. Ali is pissed off with me and the guys niggle at me like children picking on a kid at school who is wearing something different. I sit black-faced in the back of the van ignoring their antagonistic comments.

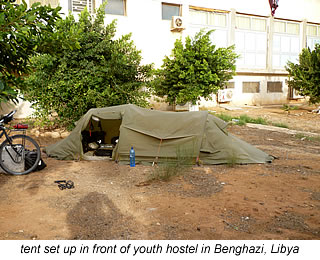

The Hostel International in Benghazi (820km mini-van trip) is closed for the night when we finally arrive at 1.30am. No night porter; no lights; nothing, so we set up the tent in the front yard. No one is awake in the morning either and after the usual breakfast and pack-up routine, we cycle off into the city to check our emails. We have contact with Barbara in Al Bayda, the only warmshowers host in Libya lined up for a visit and we need to check arrangements.

Meep meep whaaaarooom

Finding an internet cafe in Benghazi is pretty

difficult. Besides getting vague directions like a hand pointing

in a random direction, when we ask how far it is the arbitrary

answer of 600 metres kept coming up. On three occasions.

at completely different positions in the city, this miraculous

number is plucked out of the sky as the answer to our question.

After quite a bit of cycling up and down the same streets,

we eventually find the cyber café with its internet

explorer "e" painted on the wall. This is common

in Libya.

I sit outside, still feeling scarred after yesterday's fiasco, but my mood is gradually lifted by the genuine friendliness of men in this big city. I am offered a cup of coffee; given a bottle of water and upon exiting the shop owner next to the internet café picks me out a scarf.

We leave via the coast, which is slowly creeping over the highway, making cycling pretty difficult for a few hundred metres. The outskirts, sadly enough are as dirty as the rest of the ride through this area. Traffic is fast and furious. Beeping twice before rocketing past at 150 plus kilometres per hour. Meep; meep whaaroom: like a constant flow of road runners.

Kids throw stones at me along this stretch and Ali and I decide, so long as we are not hurt, we will just ignore them from now on. It wastes too much time stopping and it is a totally futile exercise, when locals believe that children are exempt from any form of responsibility at all.

It shows signs of getting dark as we climb halfway up the 4 kilometres and 268 metres of altitude gain and so we pull off behind sand hills that everyone conveniently uses to dump their household rubbish 2 km after Tukrah (81km; 256m).

Speed kills

There are lots of undulations today including the first muscle awakening

climb reaching a 291 metre peak. We roll up and down through

farmland to Al Marj [325m], a town totally under construction, and onto a high

point of 489 metres at 15 kilometres before Al Bayyadah. During this ride,

we are stopped a couple of times by men in unmarked cars wanting to check our

passports. We refuse to show any documentation in Libya until they can prove

that they are really the police. Most of the time, that means they have to

wait until we arrive at a checkpoint, but none of them really seem to mind.

Besides it is not as though we can go anywhere else. There are no other roads.

In general, the military police have been quite amicable and we haven't had

any problems so far. They are just doing what they have been told to do;

which is write down our passport numbers, names and visa information on a scrap

of paper. It more than likely ends up in the bottom of someone's desk somewhere.

Today however, we are tailed for quite a considerable amount of time and long enough for it to be quite annoying. We stop. They stop. I slow down. They slow down. We confront them in a small village, but they speak and appear to understand no English whatsoever. Their persistence in following right behind us, eventuates in us pulling off for a lunch break. They drive past and wait at the petrol station up the road. When we finally get back on our bikes, we are left alone.

The amount of traffic is again, terrible. There are so many cars on the road in Libya. Everyone must own one and I wouldn't mind betting they are just as heavily subsidised as the bread. You can get 5 large baguettes here for 0.250 dinars; that's 3 euro cents per stick. But the worst part about their road presence is the speed that they travel at. It is phenomenally scary. And with enough incidences of absolute hair brain stunts performed right before my very nose, I have invented my own theory about why.

Human beings have always been tempted by anything that makes them buzz; whether it be a physical, intellectual; or mind altering high, it doesn't really matter. Just so long as it gives a kick in some way. And in a world where alcohol and drugs are strictly prohibited and in a society that forbids the act of sex up until the day you are married, there has to be some outlet to let off steam. Libyan highways and the law enforcement's blind eye provide the perfect environment for citizens to use speed as their form of drug. But the sad thing about large doses of speed is, no matter which form of it you might consume: speed kills.

There have been very few opportunities to camp wild in this area. Farm houses dot the landscape outside the villages. The first real chances come after we exit Qasr Libya, though we have to scarper up a sharp slope to reach a perfectly hidden tier big enough for our tent: 7 km after Qasr Libya (89km; 751m).

Rich

in oil; rich in soil; rich in antiquities

The countryside becomes a bit more picturesque on our way to

Al Bayda: it is mighty hilly and way greener for that matter

too. Everyone knows that Libya is rich in oil, but I had

not expected such fertile soil as well. The benefit of this

north-eastern green belt is the abundance of organic

fruit, vegetables and cottage industry. Shops, small supermarkets and roadside

stalls dot the countryside selling the flavoursome fresh

produce.

After passing through Massah, where not one woman is sighted, I was a little skeptical about what might be in store. But Al Bayda (41km; 516m) is a thriving little metropolis and although it has just one internet café - which we actually manage to find - quite modern in feel. We arrive at 1pm and hang out in a coffee-come pizza shop until Barbara finishes work.

And what a wonderful host Barbara is, with her wicked sense of humour and generous nature. She is always thinking about what she can do to help you out as a travelling cyclist. If you are pedalling through the same country she is living in, then we both recommend that you make the effort to contact Barbara for a warmshower, a chat, whatever. And if you do happen to stay with her and the cats, she will look after you like you never have been before. You can count on it. We were entertained (The Lion of the Desert - Omar Mukthar's story); educated (The Green Book - Gadafi's story); and enchanted (Barbara's own stories).

The next day we visit Cyrene nicknamed the Athens of Africa. Greeks from the island of Thera founded the settlement around 630 BC. A local share taxi costs 0.50 Libya Dinar for the 20 odd kilometre trip from Al Bayda. Our driver automatically drops us off at the bottom entrance, so we can walk back up through, yet another fabulous ancient city. At the top entrance it is easier to get a return taxi. Setting off from Barbara's we had wondered if finding the right taxi-van might prove difficult, but locals assisted us without any problems. We were told with obvious hand signals that the van we want will flash its lights as it drives past. Sure enough it did just that. Again, we get that priviledged feeling tingle through us as we wander around such rich historical evidence of ancient city life. Again, we are virtually the only ones at the site. It is almost unbelievable.

There is plenty more to say about our visit to Al Bayda, but to be honest reinventing the wheel takes almost as long as respoking one, and I know how much time goes into that. So, why not read Barbara's story about our stopover. Honestly, it could not be put more eloquently.

With a little

help from a storm

Wind and rain are

doing some pretty extreme things as they pass over Al Bayda

the morning of our leaving. A clearing comes, bringing

with it skies of clouded deep indigo and gold. The fury

stays on the left and remains parallel with us, which

means we skip taking the coastal road to Apollonia and

the harbour ruins of Cirene. It also means the winds

are pushing us at great speed along the many rises and

falls of the highway. We have dropped hard and fast into

the coastal town of Darnah by 2.30pm and after an easy

90 kilometres, where we shop at the fruit and veggie

market for supplies. An hour later, we have peaked the

7 kilometre and 246 alti-metre climb out of town. During

the slow pedal to the top, a couple of lads thought it

would be a great joke to drive on the wrong side of the

road and play chicken with me. For a moment there, I

thought I was back in India.

Following the flat desert path all the way through to the little town of Umm Ar Rizam, there are no real opportunities to wild camp anywhere. Three kilometres out of the oversized village and 22 km before Al Tamimi (145km; 753m), we push the bikes far out into the desert distance where a ridge and solitary bush shelters us from the road and prying eyes.

Two days of remembrance

Out in the open plains of never ending sand, the wind

beats into us from a southerly direction. We are unfortunately

heading southeast, so the first kilometres into Al Tamimi

are a hard push. Here, we turn a sharp left which would normally

be great news, but the wind decides to change course as

well and we are now hammered from the side. Can't win.

A westerly tailwind helps after a small climb over a sandy crest and we are blown easily towards the turnoff to the Knightsbridge Cemetery, after a daily total of 95 kilometres. This area of Libya was one big battle field in the Second World War and the evidence is apparent with the number of war memorials. But what can you say about a war memorial? People write "Moving"; and "Lest we forget" in the visitor's book comments column. I find them quite somber places no matter how ornate or architecturally attractive they may be. The rows and rows of soldiers names all aged 20 something is remembrance enough of the craziness of war. And as far as I'm concerned looking at all these wasted lives, no-one really wins.

On the edge of a couple of freshly ploughed fields we nestle in behind a ridge, 7 km after Knightsbridge Cemetery (105km; 311m), not quite far enough from the road for my liking. The next morning, the wind is against our arrival in Tobruk. Road signs have been counting down this city every 5 kilometres, since just after Darnah. It is surprisingly modern and much bigger than I suspected. We pick up supplies just before embarking on the 6 kilometre uphill to the Tobruk War Memorial followed by some more climbing over the next 3 kilometres to reach the French Cemetery of remembrance.

A man with a walkie talkie approaches us and wants to see our passports at the last memorial. We ask for identification, but he says he has none because he is "Secret Police". His answer does bring a smile to both our faces, but until he can prove who he is - a course of action not just for Libya, but anywhere in the world - we refuse to hand over any documents. He leaves and we eventually do too. A kilometre down the road, a marked police car with a uniformed lad and the "secret police-man" pull us over. Names and numbers are copied from our passports to a sheet of paper on a clipboard.

The rest of the day's journey takes us in and out of little towns and is much the same as any other day of cycling in the Libyan desert. The wind either helps or hinders you depending on which way you bend and the road is pretty smooth with a decent shoulder, but it is difficult to find a decent camping spot. We pull a long way off the road between Bi'r Al Ashab and Qasr al Jady (103km; 296m); about 50 kilometres from the border.

The battle into Egypt

A

20 kilometre southerly side wind tries hard to keep us in Libya,

but our visa runs out today so, no matter what the wind thinks, we have to cross over into Egypt.

Libya is definitely an interesting

place to travel, owing to its spectacular ancient sites

and lack of tourists in general, but as a cycling destination

it is pretty non descript. Luckily, the prevailing southwesterly

winds pushed us along in the right direction on a few occasions

and our prayers for staying alive on the crazy highways were

answered.

Even so, we are ready to move on. A number of ill-mannered people today obviously don't want us to hang around either. We have stones thrown at us, we are given rude hand signals and one guy even spits at Ali. Making the exit out of Libya even more unpleasant, is the amount of rubbish which, as you near the border, escalates to absolutely ridiculous proportions. The one kilometre ride from Musaad village to the first official boom gate feels like cycling through a council dump.

We change money in a local store in Musaad, not knowing if there will be any other chance to do so. The exchange rate is not brilliant, but the owner swears on Allah that it is a good rate. An ostentatious border control is still under construction, so we have to make do with the old shack like rooms that official men keep slipping in and out of. I sit on the median strip across from an overturned plastic chair with one leg remaining. Each of the wrought iron garden lanterns lining the patchy wall in front of me is broken. The boom gate to my right is rusted and weighted by an old paint bucket filled with cement. Flashy cars with darkened windows pull in and out with little restraint, while we wait hoping that we are not going to experience the Libyan five minutes leaving the country too.

Soon enough we are passing through the next stage of officialdom. Before we are cycling our way down the 200 metre drop into Salloum in Egypt we will have shown our passports a further seven times. That's nine times in total. Efficiency is definitely not high on the priority list in North Africa.

The Egyptian border control is completely laughable. Ali waits in line - the word 'line' not really having the same concept in Egypt as in the western world. it is more of a free-for-all gathering, where the one who can waggle his passport closest to the nose of the official as well as shout the loudest is usually the one who gets served next. The guy in the glass booth tells Ali he has to get a visa first. In order to do this, you have to pass through immigration and customs, all of whom think you as passing by unofficially and you therefore have to stop and explain that you are not yet proceeding to enter the country, but instead you are in need of visiting the Egyptian bank to purchase a visa.

At the bank, they quote you the price in US dollars and have a problem working out how much that is in Egyptian pounds [87.25 L.E. or 15 USD]. Once you have your little stickers in your passport you return back to the passport control booth and wait for the official to come back from his tea break. In due time, he takes your passport, stamps it and drops it in a little box which connects with the booth next to him. Here, another person types the details furiously into a computer and then puts it back in the little box. In between collecting new passports and stamping them, the first official also sees time to hand back the passports, after processing, to the correct person.

While all of this is happening, I am admiring the fluffy slipper footwear on the group of women next to me. A couple of them adorn fake white Nike scuffs with matching ankle socks; another, a chequered pair similar to what grandpa would wear, while one woman parades around in furry red slip-ons with black and white panda bears. This soon gets boring, but there is not much else to look at except for way too many loitering men dressed in turbans and shalwar khamiz [long pyjama like shirts]. Ali returns with passports in his hand and while immigration takes only a few minutes, the man at customs insists on squeezing our Ortlieb bags before waving us through. Salloum (Egypt) (78km; 186m) is 12 kilometres on from the border post.

Hotel Sert, advertised on the way into town and in the Lonely Planet asks 180 Egyptian pounds for a grotty room with bathroom and sagging wire beds. That is nearly 24 euros, which is a clear rip-off. Hotel el Ahram is way grottier, a lot cheaper (€4), with the same sort of beds but without a bathroom. You wouldn't have wanted the stink of the their toilets in your room anyway. Luckily, the shop owners are honest around here, otherwise we would have nothing good to report about this village and our first night in Egypt.

New

Palace Hotel [website],

Cairo, Egypt, 04-01-11

Welcome to Egypt

Salloum to Alexandria

5 cycle days; a short rain

ride; 4 rest days; 539km; 1113m)

Salloum to 9 km after Sidi Barrany (94km; 277m)

9 km after Sidi Barrany to Mersa Matrouh (133km; 183m)

Mersa Matrouh to 18 km after Fuka (94km; 249m)

18 km after Fuka to 12 km b4 El Alamein German War

Cemetery (86km; 190m)

12 km before El Alamein @ German War Cemetery to Alexandria (132km;

214m)

Alexandria to Cairo (220 kilometre by train)

Not another Indian experience

Reports about Egypt are as varied as the prices you'll be quoted

for a taxi trip from Cairo centre to the Giza Pyramids. We are uncertain of what

to expect, but sincerely hope our travels here will not be another

Indian experience.

Hotel Al Ahram on the first night, is not promising with a urine odour in the toilet so strong, it could knock a small child out. I merely gag a few times. The bed blankets are no longer fluffy, just sticky, the linen stained and there is no hot water. Price tag for such facilities is 30 EGP (1 US = 5.81 EGP). Cheap and nasty. Camping is so much better than this, but the military presence around these parts will make that difficult. After Sidi Barrany it lightens up a bit, but just before we reach Alexandria we are questioned a few more times in a more than interrogative kind of way.

The shop owner in Salloum points us up the street, when we ask him where we can buy bread. What obviously appears to be the bakery is packed seven deep, all jostling to be served. Before Ali can get even one row in, they have sold out. Across the road will open in ten minutes, we are told. Wheeling the bikes to the opposite side, the crowd that has now started to form around us follows, but not before Ali gets a finger waggling from an Arab man who obviously has something to say, but we can't understand. Later, it dawns on me that the hole in the wall dishing out eesh [Egyptian flat bread], was probably a free bread kitchen. Maybe that was his problem.

Asking for 6 bread with a one pound Egyptian note in my hand, the baker shakes his head and says it is 3 pounds. I don't believe him, especially after Tunisia and Libya, where this daily staple is way cheaper than chips. Though, I soon learn that shop owners in the north of Egypt are pretty honest, helpful and more than happy to tell me the cost of each item. Nothing has a price tag on it and everything is slightly cheaper in this region than in Cairo.

We figure there will be something else along the way and voyage out into the strong continuous side wind that will become headwind over the course of the next few days. The road undulates softly. Besides plenty of trucks loaded to the brim with ceramic toilets and bathroom fittings, there is but one tiny store with basics 25 kilometres from Sidi Barrrany, which means we pull out the stove and cook lunch for a change. Spaghetti with fried onions, garlic and cream cheese portions. One of those instant dinners that tastes so good. Being so close to Sidi Barrany, we may as well cycle on in and shop there. The progress hasn't been particularly fast today so, if they have a hotel, we'll chance it there for the night too.

Public stoning

Plans are completely changed after moments of hitting

the main strip. Every town in Egypt has its population

of working boys. They are twelve plus year olds, no longer in

school, who have or ride around with their mates on donkey carts.

They pick up odd jobs here and there, but most of the time they

just hang around making a nuisance of themselves. The day

we venture into Sidi Barrany, they are obviously bored out of their

little brains and on the prowl.

And what better way to get your kicks than pester a woman on a fully loaded bicycle. Within minutes of them spotting us, they have circled around me and begun pushing and pulling at my bike. This is a very freaky feeling and I let them know it. Though the effect of my screaming only heightens their delight. An old man steps in and they disperse only to assemble around the shop where we wish to purchase some goods and then get the dickens out of the place. The kids just plain annoy everyone. Shop owners and locals whack them with sticks and brooms, they chase after them, throw water at them trying to control this pack. Seems they can't.

The shop owner in Sidi Barrany points me around the corner, when I ask him where I can buy bread. Hot pockets are being turned out of the metal drum oven on the wooden table which is packed four deep with kids within minutes of my arrival. I ignore the young boys ridiculously childish antics, their leg kicking, their bum pinching, but when someone throws are glowing cigarette at my neck, I go wild. They go wild too, but in a different sort of way. Shop owners are still trying to control them, but they still can't.

The sea of men and boys surrounding us part - not a woman in sight in this town. As we return to the road ready to cycle out, the kids go crazy, screaming a quite scary war cry, running in a pack beside us all throwing stones. And not pebbles either, more like stones the size of fists. This makes the hunt scene in Lord of the Flies look like a picnic. The ring leader would have no problems getting the part of Jack in the play. His laugh is wicked. I try to ignore the assault and keep on cycling, but it is a bit difficult with rocks ricocheting off me and my bike. Stones that could do some real damage to either. Ali gets hit twice and he has had enough. I turn around to see his bike dropped on the ground and him standing in the middle of the road screaming at the top of his lungs. I turn back. The stone throwing continues, though they have all hidden themselves like chickens of course.

I think the most bizarre thing is these are teenage boys and the whole of both sides of the streets are lined by grown up men who do absolutely nothing. Not a thing. It is one of the most despicable displays of human ignorance I have ever witnessed and I will never, ever forget it. One man eventually comes over and tries to shield us from the attack. Another joins him, but this is not good enough as far as I'm concerned.

I'm screaming at them now too. "These are your children. Where is your control? This is your town. You should be utterly ashamed of yourselves. They are YOUR CHILDREN for goodness sakes. WHERE is the control?" I don't know how many times I repeat myself with this line of questioning. It is obvious they have no power over these young boys.

A few cars get together to shepard us out of the city. The kids are still throwing stones from one side of the road. I stare at the vacant faces of the men on the other side. I can sort of understand that they may not have ever seen a loaded cyclist before, especially a woman. I can possibly believe that it beyond their comprehension, though this is unlikely in a town that has two mobile phone shops and a computer store. Even so, there should at least be some reaction, some sign: a look of shock, of horror, maybe even excitement, bewilderment, awe, confusion, whatever. But not a blankness as if nothing exists in those turbaned heads of theirs. An emotional void. A total void of compassion. It is a very ugly human landscape I am looking at in Sidi Barrany and I know for sure that I have a look of horror on my face.

Five kilometres out of town, while we are still buzzing from the surreal nature of our earlier situation, another group of boys taunt me again. That tongue warbling war cry is very unnerving, but not as much as when they pull at my bike causing me to fall off. Ali holds them back, while I cycle on. A couple of cars pull over and still they can't control these kids. It is pathetic. The end of the harassment is marked by a ute full of kids from the town driving past and throwing a stone at my face. The saddest thing about this incident is there are two adult men travelling with the boys. Obviously, they think this activity is perfectly acceptable. I'm lucky it was not forceful enough to injure me. And in hindsight, we are darned lucky that something more serious didn't happen from such an uncouth display of behaviour.

It's been a hard day's ride and I've been treated like a dog.

It's been a hard day's ride. Gonna be sleeping like a log: 9

km after Sidi Barrany (94km; 277m).

Christmas come early?

The day starts really early. We had promised the guards we would

be gone by sunrise. The only sheltered place we could find last

night was behind a wall. A wall with a gate. But the gate

was open, so we took the chance. With the way we were treated,

we didn't want to be out in the open. Of course the guards came

in around sunset and at first didn't want to let us stay, but

after some sweet talking from Ali, we could: on the proviso

we left when the sun rose. And it is a good thing really, because

we need every single minute on the road today.

A strong headwind turns the trip into a grind. I'm thankful for my MP3 and I further break the boredom by filming every 20 or so kilometres. Breaks up the journey into sections, which always seems to help somehow. There are plenty of scrumptious cake stops planned into the day as well. In stores all through the north of Africa, you can buy these individually wrapped mental and physical energisers. Another detail I'm grateful for.

Reaching the city of Mersa Matrouh (133km; 183m) just before sunset, we are happy to find a hotel almost straight away and one that is a notch up from our first night in Egypt. Admittedly it costs 4 times as much at 120 EGP, but we have a private bathroom and breakfast is included. Maybe Christmas has come early for us. We are beginning to think so when we learn that a local falafel bar is just around the corner. We are well and truly ready for a feast.

While the fuul [fava beans with olive oil and lemon] is not so appetising, the falafel are incredibly good. Ali goes back for a second round of these deep fried chickpea and fava bean fritters. I can't think of a more interesting dinner, than sitting at the back of this Egyptian café watching little bowls of pickled vegetables, onions, houmos and babaganoush drift past and smelling the freshly baked pocket pita as mountains of it are lifted at head height through the restaurant on flat wooden trays. Admittedly, I have noted the grot of the washing up sink, the years of caked on grime on the kitchen tiles and the ripped plastic table cloth our hot bread is plonked on, but I'm captivated just watching locals of all walks of Egyptian life come together to eat their daily meal. What a present. And then walking out of this restaurant feeling completely satisfied for as little as 40 euro cents each is just icing on the cake. A Christmas cake, I can only presume.

And so this is Egypt

The atmosphere of this town is great; people

are curious and incredibly friendly; such a contrast from our surreal

experience in Sidi Barrany. Though it is still hard to comprehend,

I guess we had best forget that ever happened. We decide to stay

for a couple of days here to rest up a bit from the dash across

Libya, celebrate our 15th wedding anniversary and to acclimatise

to Egyptian ways. Surprisingly, many people speak a few words

of English and there is usually someone around who is fluent.

If not, someone else will find another someone and drag them

away from what they were doing to help you out. In that sense,

shopping is made easy, but you have to visit lots of little stores

before you have everything you want. That can mean talking to

a lot of people and in Egypt, that takes time.

Another custom which is really hard to get used to is that shopkeepers serve everyone in the shop at the same time and you have to get in there and yell out your order too. It's like being at the New York Stock Exchange: if you don't put your bid in, you simply don't get what you want. While you are asking for a packet of pasta the man next to you - you rarely see a woman in the supermarket - is receiving his feta cheese and the one behind hollering out his desire for a scoop of olives. It is not only a confusing process for an outsider, but a long one. And it seems to take forever, but Egypt is rumoured for its Inshallah [god willing] mentality. This translates in reality as either meaning Egyptians will take an infuriatingly long time to get anything done or they will just keep putting things off until it is vitally necessary. The hand action is to hold all your fingertips together with your palm down and move your hand up and down in one or more short jerks, depending on the estimated wait I guess. Though we have only been a couple of days in Egypt, to be honest, we saw more of this attitude in Libya.

Christmas traditions

Luckily,

Christmas is not big with us. Otherwise, we may have been a

little disappointed at the long hard cycling day of strong southerly

side winds and sameness views of desert sand punctuated

sparsely with shrubs, mud brick housing, pigeon towers and barren sycamore

fig trees. Hardly the average person's Christmas Day.

The only facilities worth a mention after the Fuka turnoff - 76 kilometres from Matrouh - are the petrol stations and a few stores at about the 85 kilometre mark. They stock basic requirements and some fresh produce as well, but nothing resembling Christmas cake, I'm afraid. The landscape is not however, desolate enough to make wild camping easy. Sand dunes 18 km after Fuka (94km; 249m) near the highway are our only choice tonight and apart from a close call with a donkey cart in the early evening, we sleep undisturbed. Well, I do wake up once with a sense of something missing after dreaming of roast parsnips and champagne. Some Christmas traditions are hard to shake.

Find a pound, pick it up and all the day

you'll have good luck

A couple of revolutions down the highway

and I find an Egyptian Pound on the road and of course I pick it up. This

could mean good luck. Secretly, I hope the

side winds, though not quite as strong as yesterday, will stop.

Cycling along the northern coast of Egypt would be a cinch if

the wind is with you. Roads are good and there is a shoulder,

but most importantly, they don't drive like maniacs out in the

rural areas. As we close in on Alexandria they are as mad as

Libyans on the road, but possibly not quite as fast. No-one is that fast...

Our first bus-stop break is interrupted by a couple of boys

pulling up in their tray-top and explaining with hand signals and

mouth-blowing actions that the wind is going to change. "Yes!" I

think elatedly to myself. The Egyptian Pound is already starting its magic.

They go back the way they came, to the cluster of houses further

on ahead of us.

"How did they

know we are here?" Ali asks

"The whole village up there probably

knows we are sitting here by now." I reply.

That's just the way it works around here.

The day sees a gradual bloom in population density as we skirt around El Daba - not a good idea as going through the town would have been much quicker. We pass the El Alamein airport turnoff, miles from anywhere and cycle along the military wall, which at first looks like an attempt to rival China's building skills. It doesn't succeed, but what the construction industry lacks here, it makes up for on a grand scale in Sidi Abd El Rahmen. Apartment and resort condominiums line the coast without a single break. While those finished are uninhabited and beginning to fray at the edges, building is still continuing. The attraction of naming these accommodation areas after western girls names like Rosana, Heidi and Diana is not really apparent, except that they can put a picture of a characteristically mindless white skinned blonde on the billboard. So far, it hasn't really worked in enticing millions to live here, but we have heard that this area is devised purely as holiday homes for the rich.

A little less than halfway between Sidi Abd El Rahmen and El Alamein is the Italian War Memorial and five kilometres further on, the turnoff to the German War Graves; 12 km before El Alamein (86km; 190m), where you can conveniently camp for the evening. In fact, Moniem the caretaker, will insist you do. He will more than likely offer you access to the roof top with a marvelous view over the ocean and whatever else you may need in the way of food and beverages. Very clean bathroom facilities with a cold shower are also available. A little baksheesh [service payment] - though not at all obligatory according to Moniem - comes in handy.

Since more than 80,000 Second World War soldiers were wounded, killed or captured in the Battles of El Alamein, the region surrounding and including the town is one large war memorial. While I am no expert in this area - I'm sure my Dad could help me out here - the Second Battle of El Alamein from 23 October through to 4 November 1942 was a major turning point in the Western Desert Campaign. Allied forces broke the Axis line, forcing them back to Tunisia and eventually their eviction from North Africa in 1943. The memorials in Egypt are quite impressive monuments compared with those in Libya, though as far as I'm concerned, there is nothing particularly grand about the scale of death this blip in history caused. Just looking at name after name of 17 to 25 year old men is enough to realise what a unexplainable waste it was. And that there obviously weren't too many pennies lying waiting to be picked up.

Welcome to Egypt

Mist is thick for the first hour of pedalling.

We can hardly see 20 metres in front of us and hence not really

worthwhile visiting the Commonwealth Memorial. I completely miss

the turnoff to El Alamein altogether after 12 kilometres and only

just see the Cairo highway exit at our 15 kilometre mark. Hazard

lights are flashing and everyone is driving as slow as I am tentative.

Once the fog lifts, the extent of construction is revealed. We nickname this section Billboard Alley for the sheer number of these giant advertising plaques. We are hooted and tooted and welcomed to Egypt constantly. Traffic remains bearable until El Hamman where it increases gradually to semi-madman level as we near the city limits of Ezba Khamis (after 95 kilometres). Somewhere on this stretch and going in the opposite direction, we meet Gisele and Wilfried another couple of world cycle tourers, who have also been on the road for four years. Even more wonderous is that they don't have a blog.

From the split in the highway at the start of Ezba Khamis cycling turns into complete brain deadening mayhem and full alert madman status. So it is head down, eyes peeled and pedal like hell. At this point, we make the fatal mistake of following the highway veering off to the right, which takes us around the industrial section joining this town and Alexandria together. We should have just gone straight on instead. It would have been a lot easier and quicker.

But in saying that, we would not have had the experience of a couple of young boys leading us through the slums of town; where hundreds of cats wander freely; where rubbish is piled thigh deep; where washing and old satellite dishes adorn crumbling apartment blocks; where people live on just a few pounds a day, but still manage to smile and say, "Welcome to Egypt". I can't believe what I am seeing, because I have never seen anything like this before. There are no photographs, I didn't think it was appropriate at the time and it was getting dark fast. We still had a number of kilometres to cycle to reach the Corniche [waterfront boulevard]. Half expecting the young boys to ask for baksheesh when they see us off, they instead, jump out onto the busy market road, hold up a couple of horse carts and wave us on, saying "Welcome to Egypt".

We follow their instructions and then the directions of eight others before we make it to the Corniche in pitch black. The place is bustling, so there's no problem regarding security whatsoever, besides everyone wants to help us. Well everyone except a man outside a US$55.00 per night hotel. He is adamant that we won't find a place for 100 to 150 Egyptian pounds. Of course we do, about a kilometre up the road, which we ride partly on the side into oncoming traffic and partly on the footpath, because crossing the ten lane highway is actually impossible with a loaded bike. The traffic is constant, with no break in it for practically our entire stay at the Hotel Darwich, Alexandria (132km; 214m). I know, our room had a balcony overlooking it.

This sadly run-down British Colonial-era hotel really needs gutting completely and starting all over again. Still, it is the cheapest we can find (150 pounds) along this strip at close to 7 pm at night, with fully loaded bikes, feeling like we have just run a marathon. Besides, in a strangely quirky way, the place is kind of interesting. Plastic flower decorations, presumably not touched since 1906, are sticking out of the strangest of places, old dusty paintings randomly decorate the walls, white glossy dressing gown fabric chair covers and lace and tulle tablecloths ornament a once grand dining room which was probably packed each evening with cigar smoking gentlemen in tuxedos and ladies in hooped skirts and corsets. Today there are but a few patrons and someone of late has hung up as many fairy lights as is possible to fit in one room. Other than that fixtures remain in place whether they now work or not.